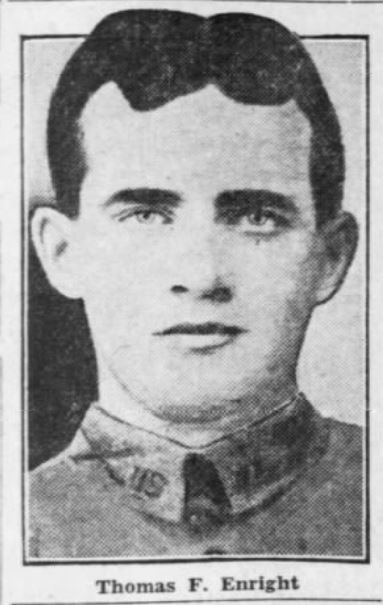

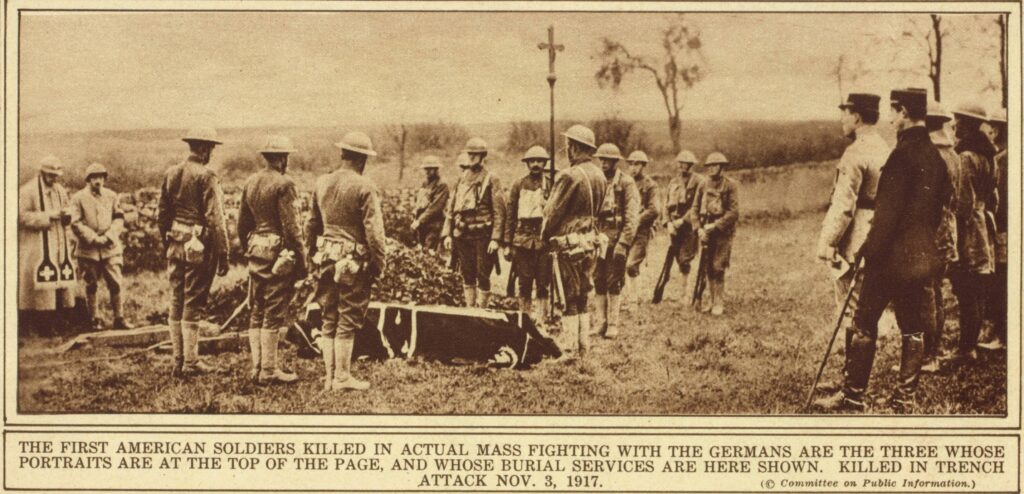

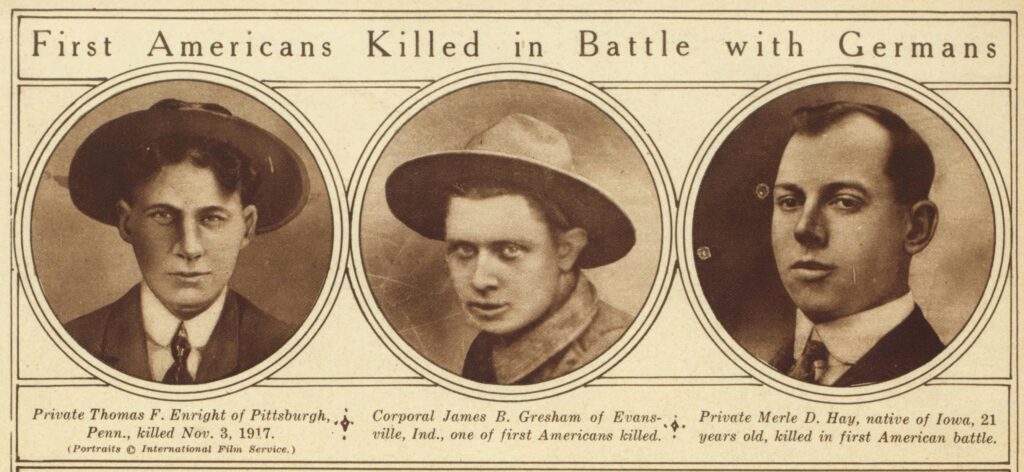

It would be impossible to reflect on Pittsburgh’s involvement in the Great War without including a bit of history surrounding Thomas Francis Enright, one of the first Americans to be killed during the war. Enright was born and raised in the Bloomfield neighborhood of Pittsburgh, joined the Army prior to the United States’ involvement in the war, got out of the Army, but then re-enlisted when the United States declared war with Germany. Enright was killed on November 3, 1917, along with two fellow soldiers of Company F, 16th Infantry Regiment, First Division; James B. Gresham from Evansville, Indiana, and Merle D. Hay from Glidden, Iowa. These three men were the first Americans to be killed in the Great War.

Despite the notoriety that would be attached to these three men, an honor not wished upon by anyone, their deaths would apparently ignite a surge in the Liberty Bond drive and sharpen the Nation’s frame of mind of ensuring that its citizens were getting behind the war effort. I would venture to guess that the people of Western PA read about Enright’s death in the newspaper, learning about how the Germans overpowered the Americans in their trenches, used brutal hand to hand combat to commit their deed, and learning that some of the soldiers in the unit had been taken prisoner during the incident. It undoubtedly struck an emotional chord with many, possibly feeling that personal connection with a local boy and relating it to someone they knew who was about to head overseas to fight. I believe it may have also been the reaction to how the French people responded to the death of these men, and their subsequent burial. Several efforts have been made over the past century to ensure that future generations in both the United States and France would honor and remember Private Thomas F. Enright and the “First Americans to be killed.”

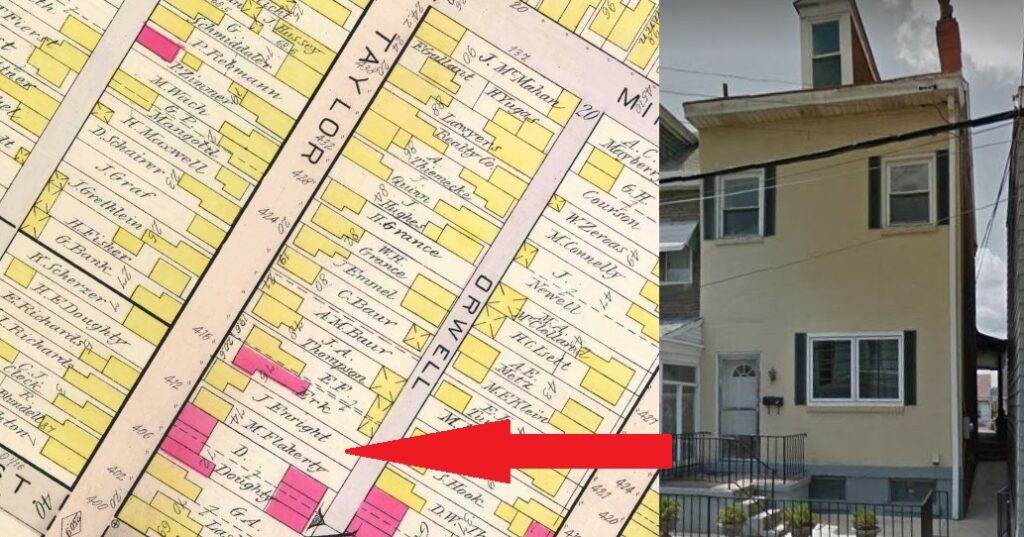

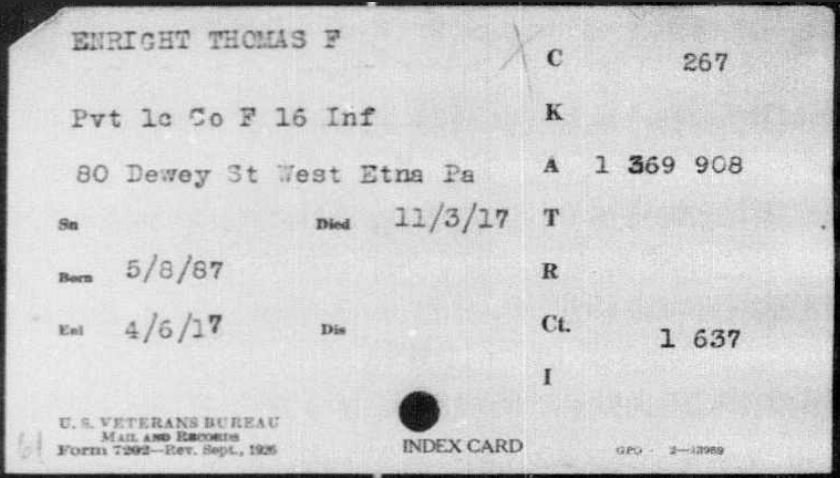

The Enright family lived at 414 Taylor Street in the Bloomfield neighborhood of Pittsburgh. Thomas Enright was 14-years-old when his mother Ellen Hern Enright passed away at the age of 49. In 1913, his father, John Enright, died in Saint Francis Hospital of pneumonia following a streetcar accident that fractured his neck and femur. Enright’s first enlistment in the Army occurred on September 15, 1909, at 22 years of age. Enright was serving in the Army in 1914 when his childhood friend from Pittsburgh, Francis DeLowery, was killed in Mexico while serving with the Marines. The Veterans Administration Master Index card for 1917 has his address at 80 Dewey St, West Etna, the home of his sister Johanna Trunzer. Enright reenlisted in the Army on April 6, 1917, the day the United States formally declared war against Germany. When the Army reported Enright’s death in November 1917, his sister Mary Irwin was living at 6641 Premo Street in Pittsburgh. She talked to the Pittsburgh Press shortly after learning about her brother’s death and said that he had enlisted “eight years ago,” referring to this 1909 enlistment. However, she reported that she had not seen him in at least 5 years. Pittsburgh City Councilman John S. Herron proposed in November 1917 of renaming Premo Street to Enright Street, but the measure never passed.

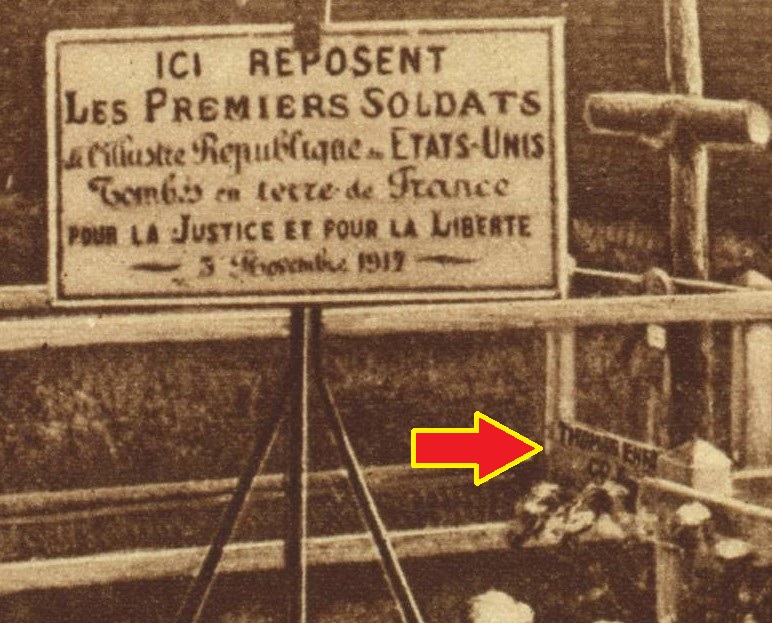

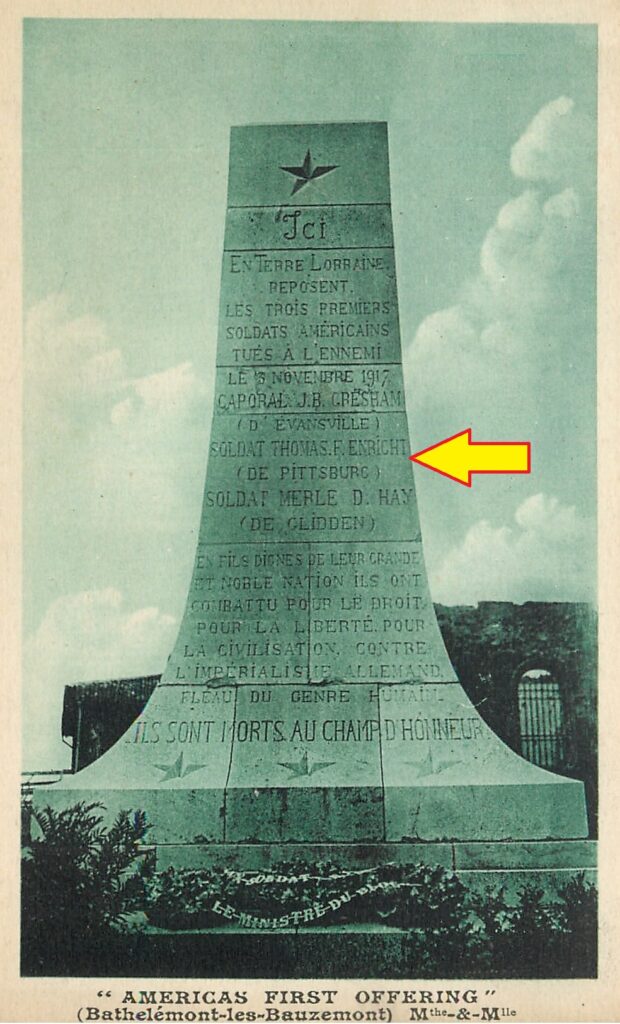

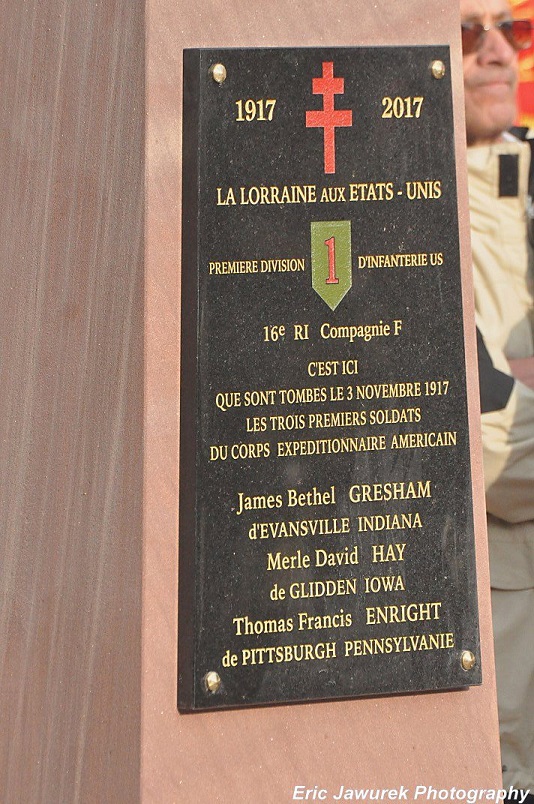

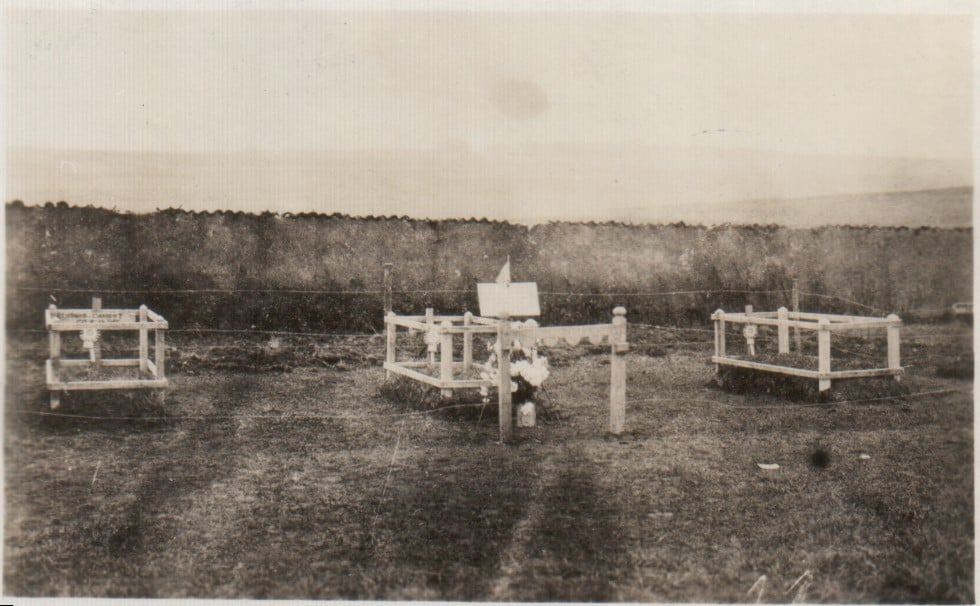

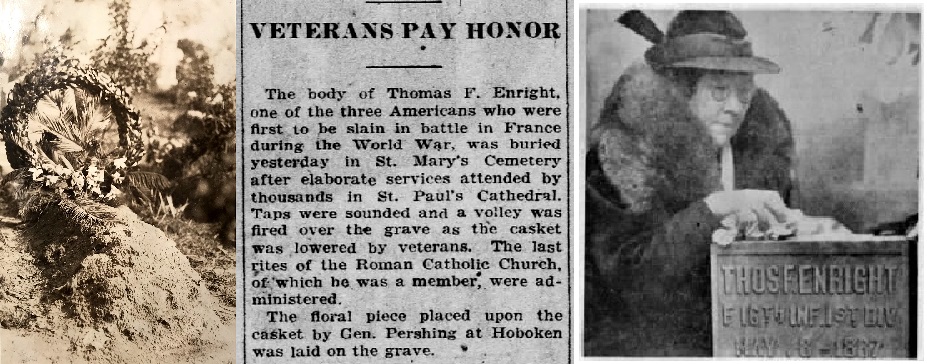

The photograph of Enright’s first burial site in France has been shared extensively, and if you look closely, you can just make out Thomas Enright’s name at the base of the wooden cross with “Co F” written below his name. Although his remains are no longer in France, there are at least two memorials in France that honor and remember his service. One monument is located at the entrance to the Bathelémont cemetery. The history of the original monument placed to honor these three men is a fascinating story. In short, the first monument was placed in the center of Bathelémont, seen below in the postcard image titled “Americas First Offerings.” However, this first memorial would later be destroyed during the Second War, October 16, 1940, when members of the German Army dynamited the monument. A replacement monument was later installed and it presently sits next to the Bathelémont cemetery entrance. A more recent memorial was created in 2017 and has been placed in the location where researchers believe the men were killed. The location of the trenches was researched by the Jean-Nicolas-Stofflet Association for the purpose of placing the centennial marker seen below on Haut-des-Ruelles hill, in the municipality of Réchicourt-la-Petite. When the men were killed, their bodies were carried off the battlefield to the nearby village of Bathelémont and buried the next day.

In 1921, Enright’s body was disinterred and returned to the United States. On July 10, 1921, General Pershing presented a wreath to the fallen at a memorial service held at the Hoboken, NJ pier. The wreath placed on Enright’s casket would later appear in this photograph that was taken at Saint Mary Catholic Cemetery in Lawrenceville, Enright’s final resting place. A headstone was placed in the cemetery, but by 1938, it was apparently deteriorating to the point that Enright’s sister Johanna was pleading for a replacement marker to adorn her brother’s gravesite. About a decade after Johanna Trunzer’s death, Robert B. Laufer of Louisville, KY, a survivor of Company F, made a plea in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette asking for a new marker, stating that the original was “so beaten by the weather and Pittsburgh’s infamous smoke and grime, that the inscription is barely legible.” In 1961, the stone marker that exists in the cemetery today was installed by VFW Post 897.

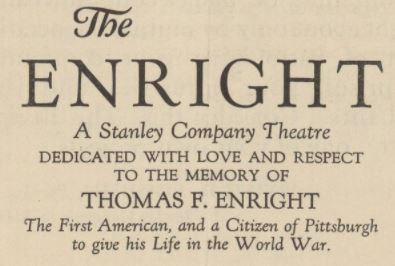

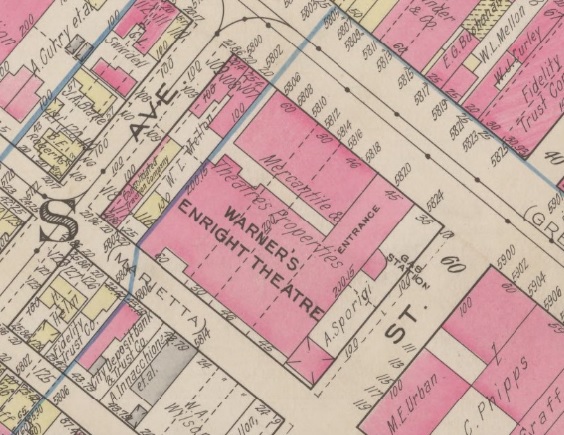

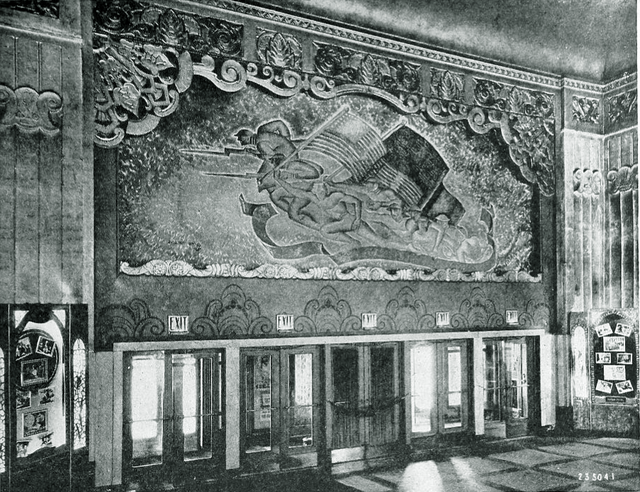

The memory of Thomas Enright was also honored when his name was attached to the theatre complex on Penn Avenue in the East Liberty neighborhood in 1928. The address at the time was 5820 Penn Avenue, Pittsburgh, but the building and theatre were razed and have since been replaced by new construction along Penn Avenue.

In 2007, Pittsburgh historian Michael Connors wrote a wonderful piece for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette about Thomas Enright, which included in the heading, “Here is the story of a forgotten hero.” Not surprisingly, the more time that passes from the years of the Great War, the less Enright’s name is even remembered in modern Pittsburgh history as it was even a few decades after the Great War. And that is all the more reason that people like myself find it so important to share his story. If we can recall his name, recall his sacrifice, we can ensure that Enright and all the fallen from the Great War be honored and remembered.

My hope is that the memory of Thomas Francis Enright will continue to resonate with future generations of people from Pittsburgh, an ever so simple gesture to ensure that we do not forget this young man. Perhaps it will be the young student reading about the Great War in school for the first time, the young researcher scanning the web about stories of how Pittsburgh honored her heroes, or someone looking to pay a visit to the cemetery and the site of his burial. Nothing would inspire me more than to know that time was allotted in a person’s day to find his burial plot in Lawrenceville, only to stop and read his inscription, saying his name out loud, “Thomas Francis Enright, you are remembered.”

Continually on the search for stories about the Great War connection to Pittsburgh, I found it interesting to learn that on the day of Enright’s initial burial in France, a young officer from Western Pennsylvania was present to witness his burial. The officer was George C. Marshall, born in Uniontown, PA, then aide-de-camp for General Pershing. Marshall, a legendary figure in American history, recalled in his memoir some of the facts about the burial that took place on November 4, 1917. Marshall wrote that General Paul Bordeaux of the 18th French Division gave an “eloquent tribute to their service,” and Marshall asked General Bordeaux if he could write down what was said that afternoon. This is what was dictated:

“Men! These graves, the first to be dug in our national soil, at but a short distance from the enemy, or as a mark of the mighty hand of our allies, firmly clinging to the common task, confirming the will of the people and Army of the United States to fight with us to a finish; ready to sacrifice as long as it will be necessary, until final victory for the noblest of causes; that of the liberty of nations, of the weak as well as the mighty. Thus the death of this humble Corporal and these two Private soldiers appear to us with extraordinary grandeur. We will, therefore ask that the mortal remains of these young men be left here, be left to us forever. We will inscribed on their tombs: ‘Here lies the first soldiers of the famous Republic of the United States to fall on the soil of France, for justice and liberty.’ We will, therefore ask that the mortal remains of these young men be left here, be left to us forever. The passerby will stop and uncover his head. The travelers of France, of the Allied countries, of America, the men of heart, who will come to visit our battlefield of Lorraine, will go out of the way to come here, to bring to these graves the tribute of their respect and of their gratefulness. Corporal Gresham, Private Enright, Private Hay, in the name of France, I thank you. God receive your souls. Farewell!”

Additional photo sources:

https://www.uswarmemorials.org/html/monument_details.php?SiteID=544&MemID=814

https://www.fondation-patrimoine.org/les-projets/obelisque-de-rechicourt-la-petite

https://www.facebook.com/US-Army-in-Lorraine-549466258485181hoto