The following article was written by the late Michael Connors, Pittsburgh Historian and former vice-president of the Lawrenceville Historical Society. It appeared in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette on November 9, 2007.

The Saturday before Veterans Day, 1984, I was driving through Stanton Heights. I came across the entire contents of a house piled along a curb. Being an antique collector, I pulled over to investigate. On top of an end table covered in the season’s first snow, there was some sort of placard. Signed by Gen. John Pershing, it commemorated the service of Thomas Enright, one of the first battle casualties of World War I. He was, moreover, born and raised in Pittsburgh. It was a historical fact that fired my imagination. I launched a quest to piece together the life of Thomas Enright, the Army private from Bloomfield who was a national symbol of America’s war sacrifice.

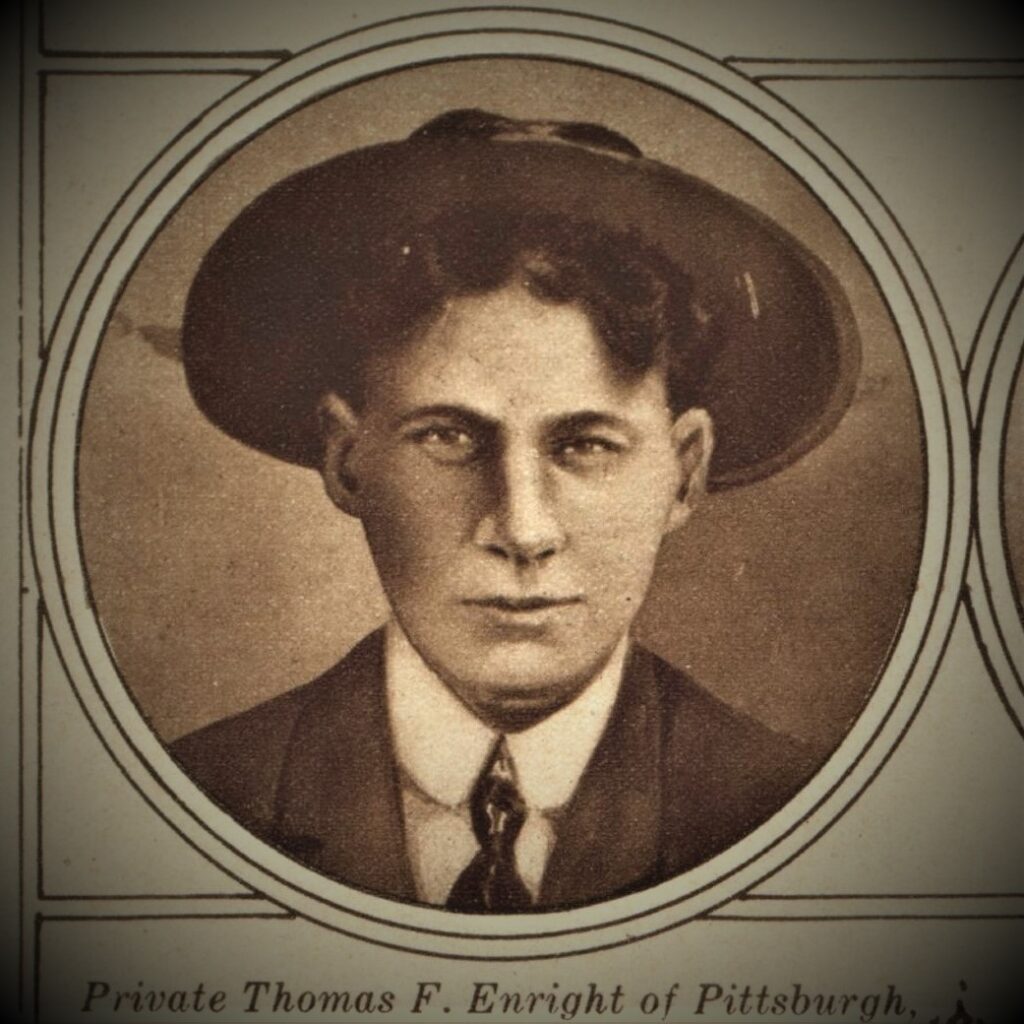

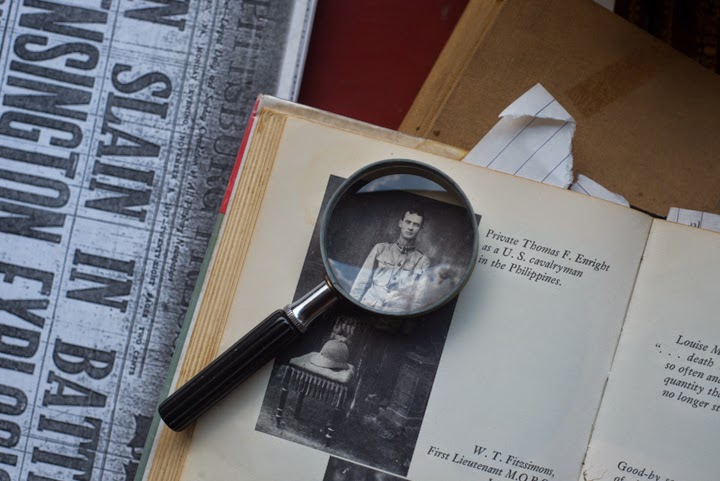

Thomas Enright was born May 8, 1887, on Taylor Street in Bloomfield. He was the seventh child (fourth surviving child) of Ellen and her considerably older husband, John Enright. Thomas was their first child not born in their native Ireland. He spent his youth on Taylor Street. While the construction of Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Hall was under way, a few weeks before the start of the 1909 World Series, Enright enlisted into the very small U.S. Army. It was the inaugural season of Forbes Field when Honus Wagner and the Pirates defeated the Detroit Tigers led by Ty Cobb. By the end of his second enlistment and return to Pittsburgh, Enright had an impressive record. He had been to China, post-Boxer Rebellion. He had earned the title of expert cavalryman, fighting Moros in the Phillippines. In 1914, as part of the 16th Infantry, Enright was one of the troops in Vera Cruz harbor when seaman Francis DeLowry was shot from the mast of the USS New Hampshire. DeLowry had been a classmate at St. Mary’s in Lawrenceville. In 1916 Thomas Enright was back in Mexico. Though he wrote to his sister Mary of seeing nothing but starving cattle, he was part of the Pershing-led punitive expedition in pursuit of Pancho Villa. After a short time back in Pittsburgh, perhaps out of a sense of duty, hearing talk of U.S. involvement in Europe’s war — or a good look at his brothers’ lives as industrial laborers — Enright re-enlisted. He rejoined the 16th Infantry stationed in Fort Bliss, Texas, just in time to be sent back across the country by rail to Hoboken, N.J. The 16th Infantry, 2,600 strong, not unlike the rest of the Army, was made up largely of new enlistments. Many were expecting a Boy Scout-type adventure. That adventure began with a two-week crossing of the Atlantic Ocean as part of the very first troop convoy. On June 26, 1917, they disembarked in St. Nazaire, France, as part of the First Infantry Division. Their chief of operations would become well known to history — it was George C. Marshall of Uniontown. The First would come to be known as “Pershing’s Darlings.” The best damn division in the Army, Pershing would call them. When the French government requested a U.S. military presence for a Fourth of July ceremony, Pershing ordered Enright’s battalion from the 16th to Paris. “The first appearance of American combat troops in Paris brought forth joyful acclaim from the people,” wrote Pershing in his memoir. At this occasion, a U.S. officer to declared — to acknowledge France’s key role in the American Revolution — “Lafayette, we are here!” (It’s possible that Pershing himself uttered it.) Four months after that proclamation, the U.S. Army was for the first time at the front. Company F, 16th Infantry, to which Enright belonged, had been in the trenches only a few hours. The Germans were aware of their presence, having been informed by a French deserter. A little after 3 a.m. on Nov. 3, 1917, the Germans launched a nearly hour-long “box assault.” This was an artillery assault to the left, right and rear of Company F’s position, cutting them off from reinforcements or retreat. Across a frozen no-man’s land, 200 seasoned German shock troops advanced with the odds 10 to 1 in their favor. Eleven men of Company F were taken prisoner. Five others were left wounded. Pvt. Merle Hay, Cpl. James Gresham and Thomas Enright were killed. Hay was shot, stabbed and stomped to death. James Gresham was shot between the eyes. A few yards away lay Thomas Enright, expert cavalryman, face down, his head nearly severed from his body by a trench knife — a 20th-century weapon little improved upon since the days of ancient Rome. Scattered in and about the trench were a few German helmets and rifles. The Pittsburg (as the city was spelled at the time) Press quoted a French general: “You fell facing the foe in a hard, desperate hand-to- hand fight.”

On Nov. 5, 1917, Enright, Gresham, and Hay were buried in the country where they had died, with the following inscription to mark their graves in the Lorraine region: “Here lie the first soldiers of the illustrious Republic of the United States who fell on French soil for justice and liberty.” The deaths of these three men would solidify the country’s resolve, becoming a notorious episode in U.S. military history. Enright, Gresham, and Hay were no sons of privilege. They could have been any farmer’s or millworker’s boys. There was a spike in war bond sales. Cheeks stained with tears, soldiers fired large French 75s (artillery pieces) in the direction of the German lines with “a prayer they would hit their mark,” wrote The Pittsburg Press. A banner headline from a local paper on Nov. 5 was “Huns Kill Local Youth.” At the election night smoker of the Pittsburgh Commercial Club, plans were laid for raising funds to build a memorial to Enright. Every person in the city would be asked to contribute the number of pennies corresponding with their age. Councilman John S. Herron introduced a resolution to rename Premo Street in Morningside, where Thomas’ sister Mary lived, “in honor of the dead patriot.” “I know that if he had a moment of consciousness before death came, he was glad to go the way he did,” the papers quoted Mary. Mary wired the War Department asking for Enright’s body to be returned, as did Mayor Joseph Armstrong and the United Spanish War Veterans. Despite their requests, Thomas Enright would lie in a French grave for over two years after the Armistice was signed.

On July 10, 1921, on the same Hoboken Pier from which Thomas Enright and his comrades had departed, Gen. John “Blackjack” Pershing stood straight and square to greet the transport ships Wheaton and Somme, which carried the bodies of Thomas Enright, James Gresham and Merle Hay. More than 7,000 flag-draped coffins were unloaded from the two ships. When carried onto the embarkation pier, they stretched row upon row. Never comfortable as a public speaker, Pershing spoke with measured voice but with visible emotion: “These men who died on foreign soil laid down their lives for us. They fought for freedom and for eternal right and justice, as did the founders of the great American Republic before them. “They gave all, and they have left us their example. It remains for us with fitting ceremonies, tenderly with our flowers and our tears, to lay them to rest on the American soil for which they died” Pershing gently laid a wreath on the coffin of Gresham, Hay and Enright. On July 14, Enright’s casket arrived in Pittsburgh at Pennsylvania Station, accompanied by William Wiggans, one of the very few of Company F to have survived the box assault intact. Comrades of various veteran organizations and a squad of motorcycle policeman were present. The body was taken to the home of Enright’s sister, Mrs. Charles Trunzer, in West Etna. The following day, Enright’s casket was delivered to Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Hall where, like Francis DeLowry before him, he lay in state. Throughout the day, a steady stream of mourners arrived, not only those who knew him, but those who knew him only as a rallying cry. Dozens of floral arrangements were delivered. On Saturday, July 16, Enright’s flagdraped casket was carried on the shoulders of his pallbearers through the front door of Soldiers & Sailors Hall. All were alumni of St. Mary’s school and veterans of the Great War. Enright was carried down the long walkway and placed on a gun caisson drawn by six horses and taken to St. Paul Cathedral for the service. During the formation of the procession, headed by a detachment of 500 ex-servicemen from the Pittsburgh police and fire departments, “the great crowd stood in silent tribute … many wept unashamed,” The Pittsburg Press reported. The cathedral could not accommodate the overflow crowd. Thousands crammed their way inside, filling the aisles. Most waited outside while a Mass was said by Bishop Hugh C. Boyle. From Oakland, the procession made its way to St. Mary’s Cemetery in Lawrenceville, where after multiple conflicts and thousands of miles, Private Thomas Francis Enright was buried again, not far from where he had been born. Pershing’s wreath was laid upon the freshly mounded earth.

If the Pittsburgh Commercial Club did collect pennies, the Enright memorial was never built. However, the Enright Theater was dedicated on a pleasant, unseasonably mild Saturday in December 1928 more than 11 years after his death. A parade launched the opening ceremonies for the theater. The 324th observation squadron flew their PT Army planes low across the sunny sky dropping wreathes upon the theater’s roof. Thomas’ sister raised the flag to the top of the gleaming new flag pole, while the 107th field artillery drum and bugle corps from Elizabeth played the national anthem. The civic-conscious crowd stared in disbelief as the first volley shattered the windowpanes of the new box office. The last 20 cannon blasts broke dozens more windows, roaring implacably on over the screams of police and populace. In a span of less than 30 years, all of the theater’s windows would be broken again. This time intentionally and for good, the flagpole from where Old Glory had been raised would be razed by urban planners. By the time of the demolition of the Enright Theater, Enright’s tombstone had become worn and illegible — due in part to the quality of Pittsburgh’s air. On Memorial Day, 1961, through the efforts of VFW Post 897, headed by Commander Joseph Borkowski, a new stone was unveiled. Some residents of Premo Street objected to Councilman Herron’s proclamation to rename the street. Today, Premo Street is Premo Street. Along the border of East Liberty and Friendship, roughly two blocks west of the site of the Enright Theater, today sits Enright Parklet, discernible by a piece of wolmanized lumber fashioned into a sign. The swingset and slide is too small to be a park. Thus “parklet.” Off Broad Street in East Liberty is Enright Court, a group of homes built during the urban revitalization that tore down the theater and created the East Liberty circle. There is irony in the city having named a dead-end street for Enright. I asked several residents of Enright Court who had spied me looking at their street sign if they knew who, or what their street was named for. They had no idea.