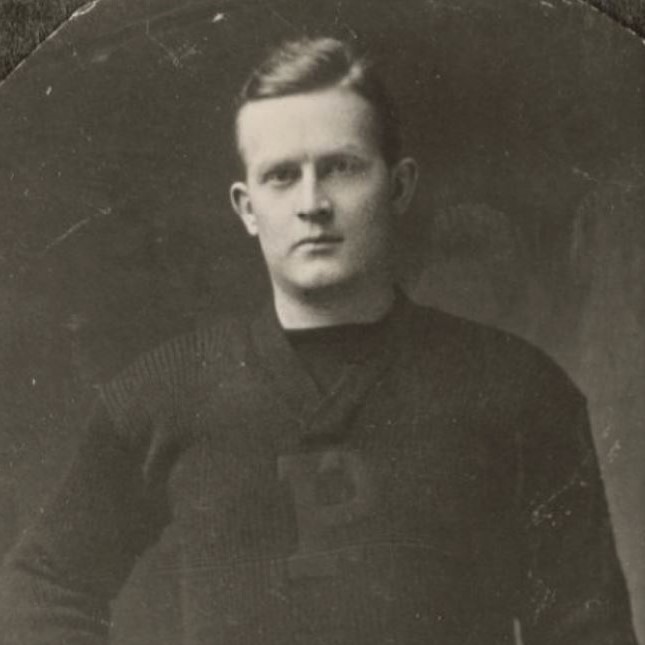

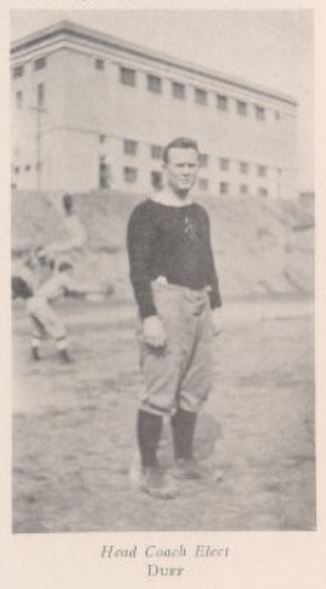

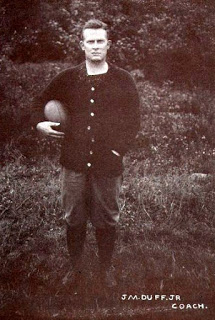

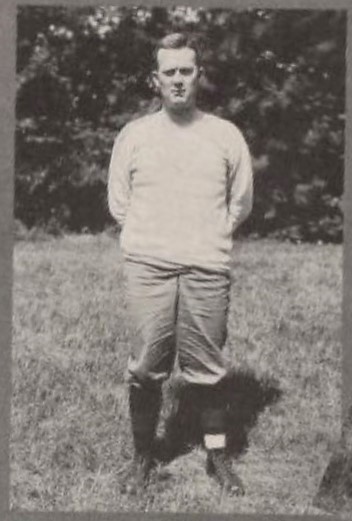

Joe Duff was destined to lead men. But like so many brilliant young men of their time, his life was cut short on the killing fields of the Meuse-Argonne. Duff was not only an All-American football player, he was an American hero. Joseph Miller Duff Jr. was an Ivy League graduate, the Head Football Coach for the University of Pittsburgh, an attorney for the Allegheny County Bar in Pittsburgh, and a World War I machine gunner. Joe Duff was an American hero. Despite being rejected by the Army on three different occasions for medical reasons, Duff was determined to serve his country and was eventually able to convince the local draft board to overlook his vision problems. Duff was a 1912 graduate of Princeton University. As a standout player on their varsity football team, he was named a 1911 ‘All-American’ and proclaimed to be one of the ‘greatest guards in football history’ according to a 1913 Pittsburgh Press newspaper article.

After graduation, he was asked to stay on at Princeton to serves as an assistant football coach. The following year he received an offer to become the head football coach at the University of Pittsburgh. Duff delivered two winning seasons for Pittsburgh in 1913 and 1914. Following the 1914 season, Pitt found an opportunity to hire legendary coach Glenn Scobey “Pop” Warner. Coach Warner helped Pitt win the College Football National Championship in 1915. That same year, Duff obtained his Law Degree from the University of Pittsburgh and went on to work in his brother James Duff’s law firm. At the time of the national draft registration, Duff was already a college graduate. He enlisted in the Military Training Association and was situated at the Reserve Officers Training Camp at Fort Niagara in June 1917. At the end of his training at Fort Niagara, NY, he was not assigned to a specialized unit as many of the other candidates listed on the roster. His vision problems likely kept the Army from granting him a commission.

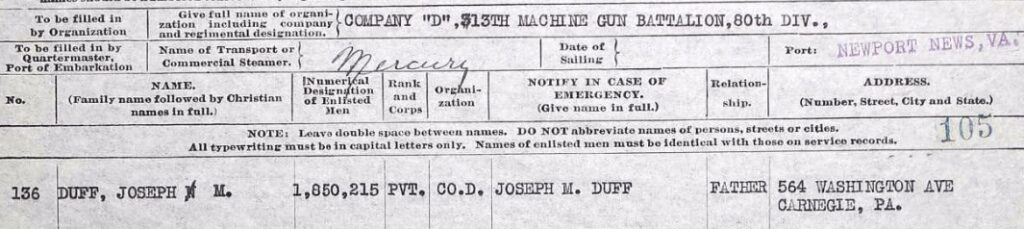

In December 1917, Duff worked as an attorney for the United States Justice Department and was responsible for prosecuting men who attempted to evade the draft, the so-called “slackers” as they were often called in the newspapers of the time. However, this role as a government prosecutor did not protect him from being called up under the terms of the Selective Service Draft. When his draft number was called in Carnegie, PA, he took the opportunity to persuade the draft board to waive his medical condition and allow him to be inducted into the Army. He was sent to Camp Lee, Virginia in March 1918 and joined with Company D of the 313th Machine Gun Battalion, 80th Division. Duff set sail with the Battalion aboard the USS Mercury in May 1918 as a Private. In less than one month he was promoted to Corporal. His prior military training to become an officer at Fort Niagara surely made Duff stand out among the other men. Duff was soon promoted to the rank of Sergeant as part of his machine gun battalion.

His tenure with the 313th Machine Gun Battalion took him into action in part of the Artois Sector of France from July 23 to August 18, 1918, and in the Saint Mihiel Offensive Corps Reserve from September 12 to 16, 1918. During my research for the book “Good War, Great Men.” I uncovered letters written by Duff’s commanding officer that revealed this officer’s fondness for Sergeant Duff. Commanding Company D was Captain William George Thomas, a 1909 graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Thomas was the former captain of their UNC varsity football team and recognized Duff within the ranks of D Company. Thomas wrote letters home recalling that Duff was once hired by UNC to coach their football team (1915 season).

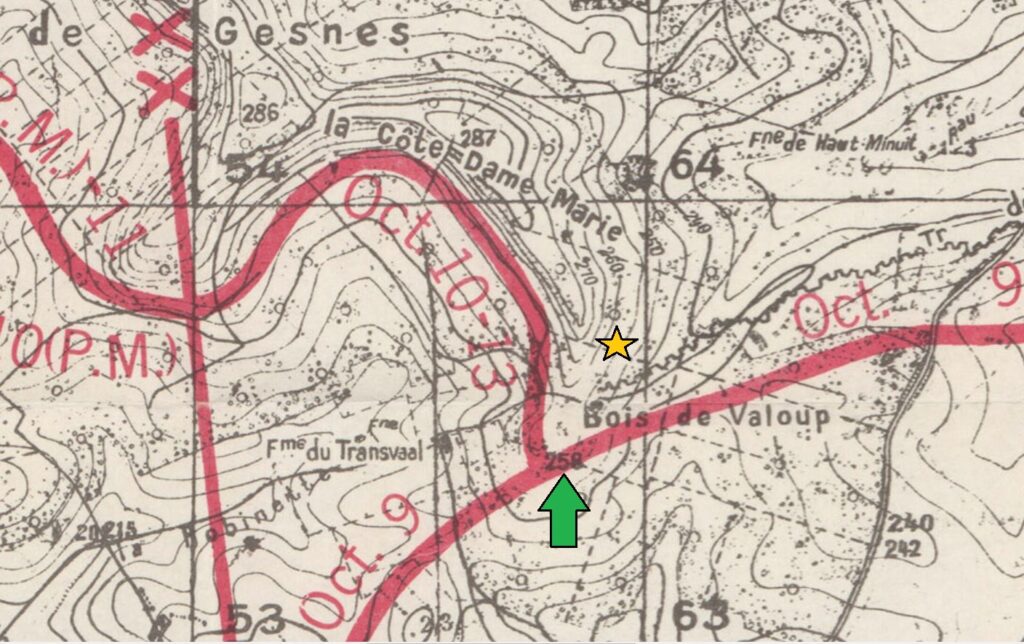

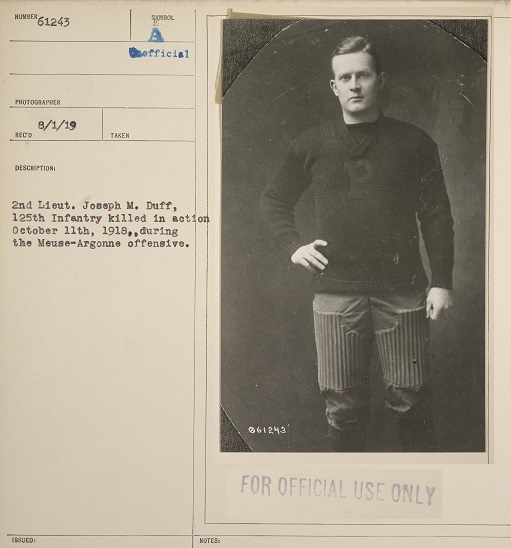

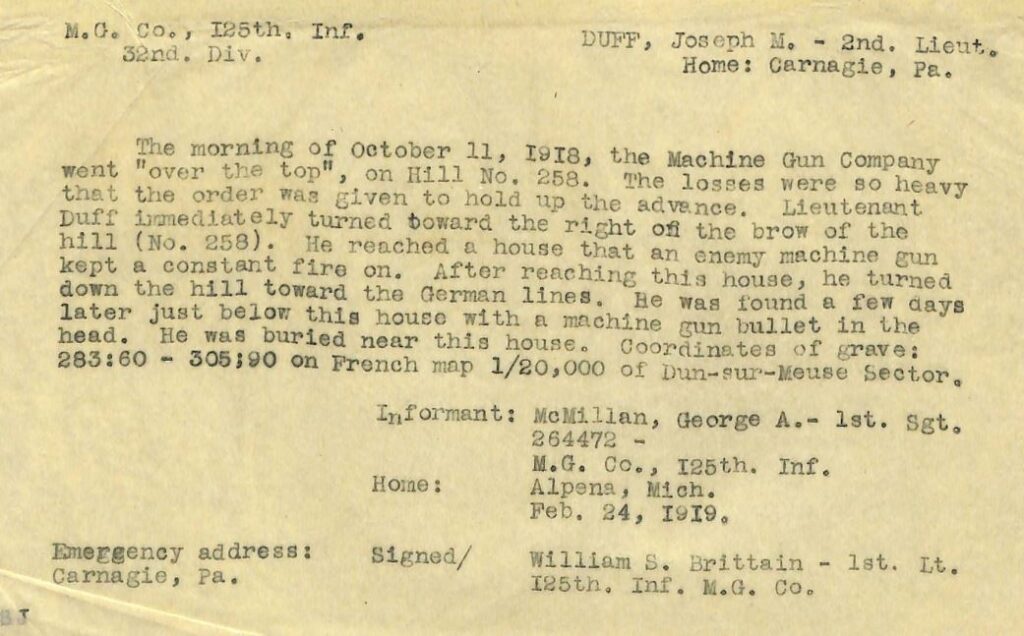

The officers of the A.E.F. were frequently being asked to provide recommendations for men within their ranks who could be sent to officers training camps in France to lead other men. Captain Thomas recommended Duff for officers training, and on September 30, 1918, Joe Duff accepted his commission as a Second Lieutenant and was assigned to lead a machine gun company in the 32nd Division, 125th Infantry. After only ten days with his new unit, Duff was killed while fighting at Gesnes-en-Argonne, part of the Meuse-Argonne offensive. His ‘Red Arrow Division’ engaged German troops east of the Meuse River until the Armistice was signed. The 32nd Division suffered a total of 13,261 casualties, including 2,250 men killed in action during the war, making it third in total number of battle deaths among all U.S. Army Divisions. Duff’s body was buried in a temporary gravesite on Côté Dame Marie in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, France.

Lieutenant Duff’s brother, Captain George M. Duff, a Chaplain serving in France with the 305th Infantry, sent a telegram back home to his brother James to notify the family of Joseph’s death. The remains of Lieutenant Duff were returned to the family about three years after his death and a funeral service was held on September 9, 1921, at the First Presbyterian Church in Carnegie, Pennsylvania. Duff’s brother George, then pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Elwood City, presided over the funeral and his remains were interred in the Chartiers Cemetery in Carnegie, Pennsylvania. The symbol on the top of the headstone represents the 32nd “Red Arrow” Division for which he served in World War I.

His brother James H. Duff later become a prominent figure in Pennsylvania politics and served as the 34th Governor of Pennsylvania from 1947-1951 and also a United States Senator from Pennsylvania 1951-1957. Brother George M. Duff served as pastor of the Riverdale Presbyterian Church (Riverdale NY) from 1922 – 1954. The Manse located on church property was renamed the Duff House in honor of George M. Duff, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

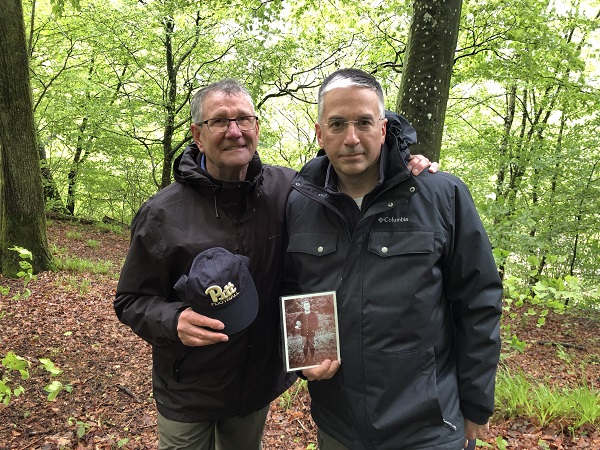

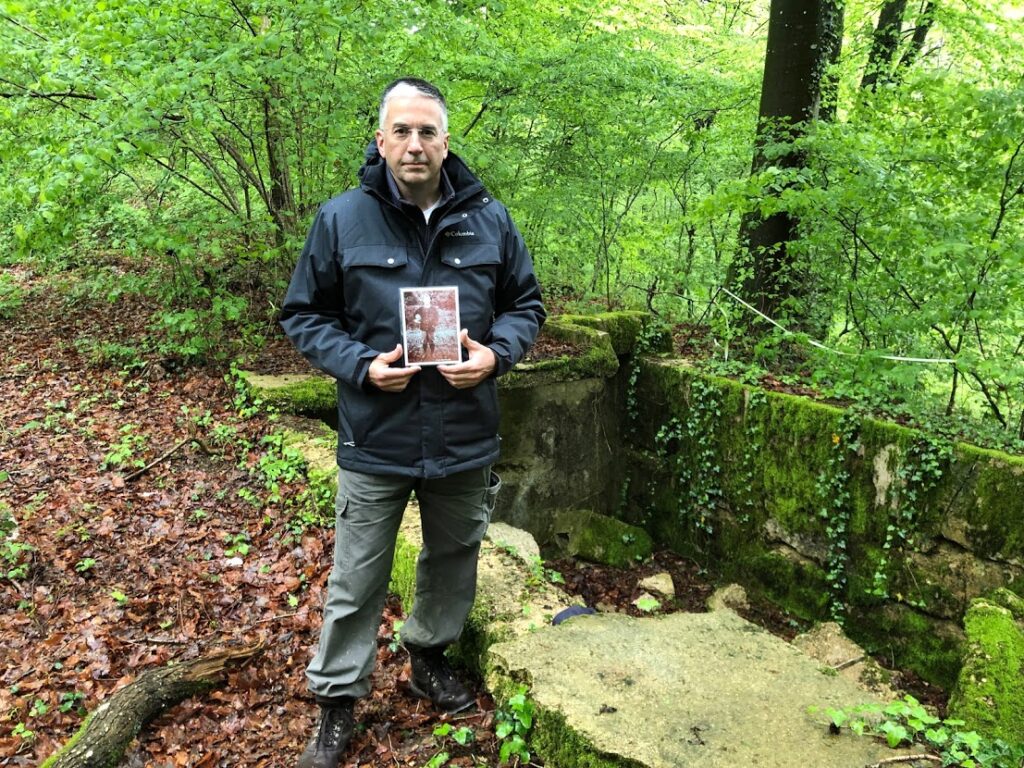

Joe Duff was truly an ‘All American’ in every respect, and it is with great honor that we remember his sacrifice during the Centennial Anniversary. In May 2019, Mr. Dominique Lacorde took me to the location where Joseph M. Duff Jr was killed and later buried. The Rev. Joseph M. Duff Sr traveled to Gesnes-en-Argonne in July 1920 to this exact spot. He later wrote this passage in his book A Gold Dollar, Studies in Nature and Life.

“Joe’s men, from the shelter of their fox-holes, anxiously watched him go forward, revolver in hand, crouching, round a little black house that still stands on the crest of the hill, and disappear on the other side. The minutes passed. He did not return. Two days later they found him, a hundred feet beyond. He had been caught in the hail of fire that swept the hillside, and instantly killed.

I walked over the top of the hill, round the little black house, and a hundred feet beyond. I reached the spot. It was strangely blank and meaningless. There was nothing to see but a mass of undergrowth. There was not a footprint. There was not a scar of shell. There was no human association, save a yellow raincoat flattened out on the ground. I could not believe that the scene of an intimate event, whose dark shadow had fallen three thousand miles away, could give me on the spot no trace of it, no message from it. A gaunt great oak near, with a shell-broken limb dangling at its side, seemed the sole witness that a tempest of fire had swept the hillside.

Adding to my surprise was a curious, brooding silence. There was neither voice, nor twitter of birds, nor rustle of leaves, nor even the break of padded feet of a scared rabbit scurrying out of the bush. I had noticed before, an absence of sounds in the fields and roads and in the village streets.

The stillness of the thousands sleeping in their quiet graves in the great cemetery had seemed to spread like a contagion over the entire countryside. But here on the battlefield, where had roared such thunder as hardly ever had been heard, the silence was eerie, as if the ghostly guard of the place had commanded it. Nature here, in shrub and tree and rock, stood rigid and still with her finger on her lips. Where war had loosed all her frightful voices, the only sound I heard was the faint rasp of a hoe in a ploughed field near, where a patient peasant, with his little daughter, was back at his toil.

I stood there so disappointed and benumbed, without even the poignant stab of pain which was my due where my boy had suffered, that to break the spell, I took from my pocket the letter of the regimental chaplain written on the day he buried him, and read it once again.”