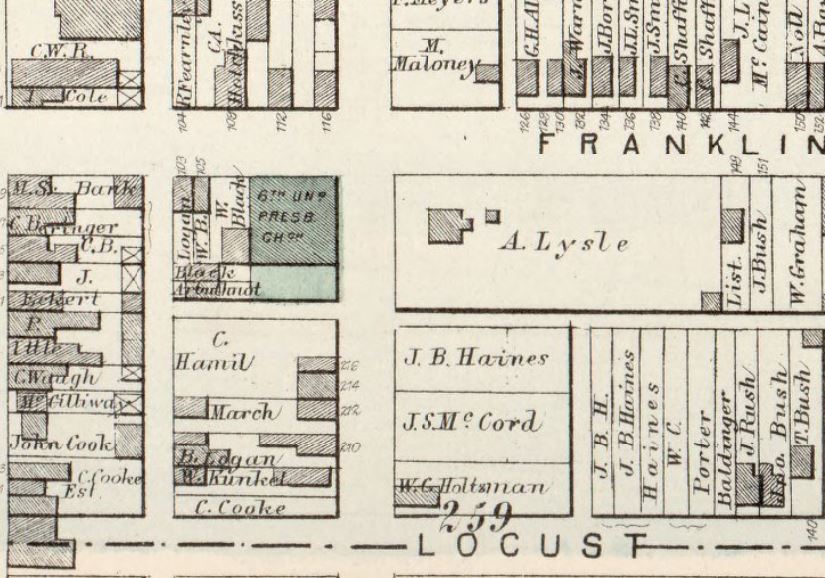

At the corner of Chateau and North Franklin Streets, in the Manchester neighborhood of Pittsburgh, there once stood a three-story home built in 1865 by Allison Lsyle, a coal barge captain who operated a successful business of delivering coal up and down the Pittsburgh Rivers. The once-grand home, with marble fireplaces and walnut woodwork, would later become the residence of the Edward William Demmler family in the heart of Manchester. The home was flanked by two churches, making this corner of Pittsburgh a lively district in “Old Allegheny” for many years. This property is of interest because it was once the home of celebrated Pittsburgh artist Frederick A. Demmler, one of the many young Pittsburghers, full of enormous promise and potential, who had his life cut too short on the battlefields of Europe during the Great War.

“Their names, ultimately, will pass into oblivion, as all names except a favored few, must pass, but no years can efface their deeds, and they, though forgotten, will live forever in the immortality of their service.”

Unidentified author, from “They Who Return Not.” Saint Louis Globe-Democrat, November 16, 1918

The suggestion to research Frederick A. Demmler came to me via a social media message. Demmler was a soldier from the Great War that I was unfamiliar with, but the more I uncovered his story, the more I questioned why, as the quote above eluded, was he one of the favored few? With just a few online searches, I quickly discovered that Demmler would not be one to fall into oblivion, and we can acknowledge the many who knew him for creating works that honor and remember their friend, Fred A. Demmler.

In my initial search, I came across a portrait painted by Demmler that I recalled seeing two years ago in an article written by historian Jennie Benford for the Western Pennsylvania History Magazine, Vol. 100, No. 4. It was about World War I soldier and poet Frank Hogan. The article discussed a two-book set printed in 1918 titled The Soldier’s Progress and Carnegie Tech War Verse. The books were edited by English professor Haniel Long of the Carnegie Institute of Technology (present-day Carnegie Mellon University), who once sat to have his portrait painted by Fred Demmler. The impression that Demmler left on Haniel Long was obviously an impactful one, enough to carry the memory of the young artist into a literary piece written in 1935 by Long called Pittsburgh Memoranda. Long wrote a chapter about Demmler in his book, along with other Pittsburgh notables such as Andrew Carnegie, John Brashear, George Westinghouse, and Stephen Foster.

I also discovered that composer Harvey B. Gaul wrote a piece of music in 1919 for the organ titled, “Chant for Dead Heros,” published as a dedication to Sergeant Fred Demmler and Corporal Francis Hogan. These works illustrate an effort to memorialize and ensure that Fred Demmler would be remembered by future generations. But the central piece of literature I found to best understand Fred Demmler was written in 1919 by Lucien Price, titled Immortal Youth: A Study in the Will to Create, published by McGrath-Sherrill Press. This literary work gives us a personal look into stories about Demmler, written by his dear friend, which ultimately challenges us as readers to keep the memory of his friend living, not by his art alone, “but by the living deeds of you.” Price writes, “Why should I point him out to you among the millions?” I again come back to the quote illustrated above, “except a favored few,” because I believe we are fortunate to have the work of Lucien Price, a successful writer, and journalist, made available to us through Project Gutenberg, and I encourage you to read the dedication to Demmler in its entirety.

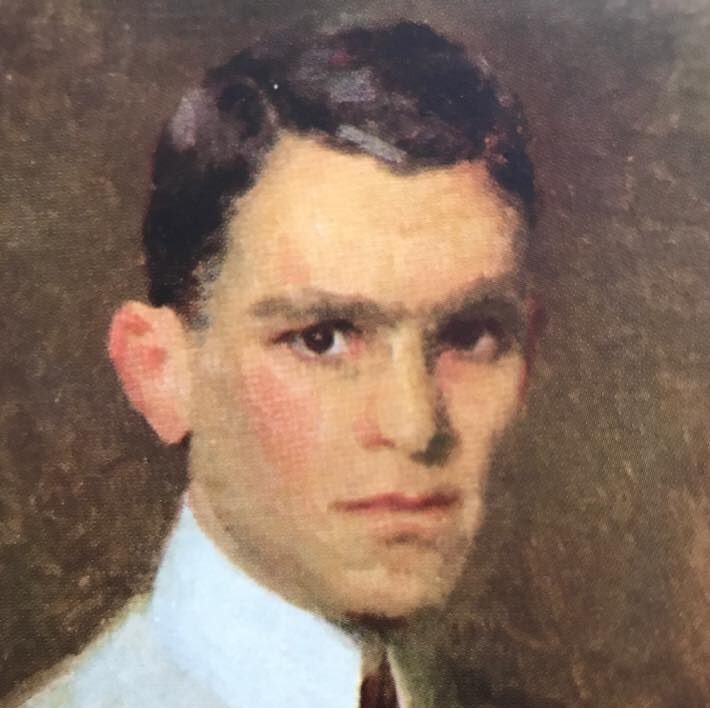

As an artist, Demmler left behind a body of work that we can certainly appreciate today. I discovered a Facebook community page dedicated to the memory of Fred A. Demmler that includes several photographs of his work that have been made available through this social media page. But what I believe I have learned most significant about Demmler, absent his artistic talent, was how much he was admired by his friends and the influence that he ultimately left on others. This fact became evident as I explored the writings and histories left behind as tributes to his memory.

Frederick “Fred” Adolph Demmler was raised in the Old Allegheny neighborhood of Pittsburgh (present-day Manchester) by his mother Wilhelmina “Minnie” Demmler, and his father Edward William Demmler, who served as president of the Demmler & Schenck Company. By all accounts, the Demmler family lived a comfortable life as a result of the father’s successful business providing kitchen appliances and equipment to the Pittsburgh region.

Fred Demmler grew up in a household with six brothers and one sister, and was afforded the opportunity to study his craft and hone the skills needed to prepare himself for making art his livelihood. Given the opportunity to live anywhere, Demmler chose to stay in Pittsburgh. He told his friend Price, “I want to paint, and I do not want to have to play social politics in order to get commissions, as I am afraid I would have to do in Boston. Besides, in Pittsburgh, there are fewer painters to influence me. I stand more chance of being myself.”

He once served as vice president of the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh, first organized in 1910. His painting “The Black Hat” was selected for exhibition in The Carnegie International. In 1916, his portrait titled “Vera” won third prize in a competition and was selected by One Hundred Friends of Pittsburgh Art to be placed in a Pittsburgh public school for observation and study by the students.

Shortly after Demmler completed his initial studies in the United States, he took a trip to Europe to explore and study many of the great works of art found in their museums and galleries. When Germany invaded Belgium in 1914, and Great Britain issued an ultimatum demanding that Germany withdraw its troops, Demmler was part of the crowd that gathered outside of Downing Street waiting to hear what would happen next. When the deadline given to Germany passed without a reply, Britain declared war. Demmler told his friend Price, “It gave one an odd feeling to realize that behind those drawn shades sat men who were settling the question of life or death for hundreds of thousands of their fellow creatures. The crowd cheered. I did not.” Four years later, Demmler would be buried in Belgian soil, just nine days before the end of the Great War.

Demmler returned from Europe to work at his craft. He painted in a studio on the grounds of the family homestead, the house at the corner of Chateau (formerly Chartiers Street) and North Franklin Streets. The house is now gone, but what does still remain on the property is a two-story brick building that once served as Demmler’s painting studio. It was considered the playhouse for the children. Demmler also rented a studio in the Garrison Building at the corner of Third Avenue and Wood Street. This building has been razed and is now a courtyard on Point Park University property.

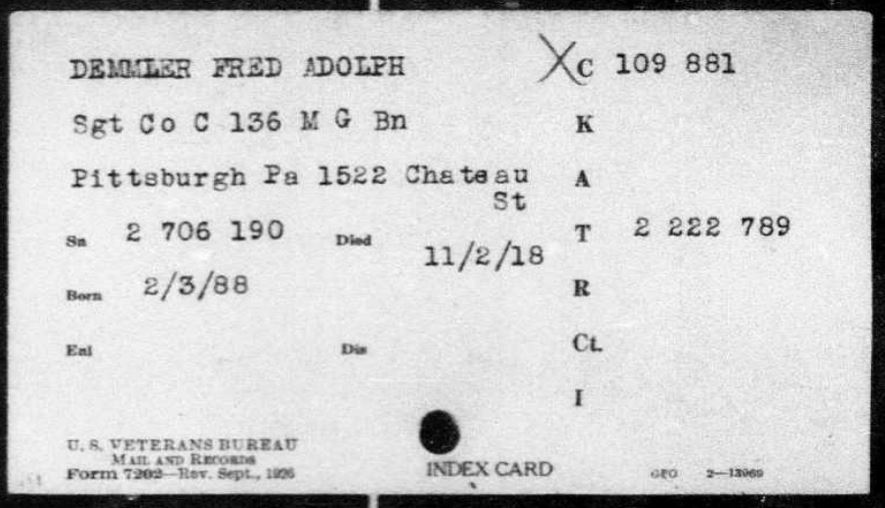

To appreciate Demmler’s character, I found it admirable how he approached his war service. When completing the draft registration card in June 1917, each registrant was asked, “Do you claim exemption from the draft?” Fred Demmler wrote, “Conscientious Objections.” Price wrote about his friend’s struggle with war and conscription, but once Demmler was placed into the ranks, this objection did not appear to impede his disposition, and he was soon identified as a leader among the men while serving at Camp Lee. He was eventually advanced to the rank of Sergeant and a platoon leader in Company C, 136th Machine Gun Battalion, 37th Division.

But Fred Demmler wasn’t alone with his struggle on the concept of going to war. Of the seven brothers, four were required to register for the initial draft, and at least two brothers claimed exemption based on conscience. Brothers Paul, Walter, and Alfred fell outside of the first draft age requirements (men 18-30 years) so we don’t know how they would have answered this question.

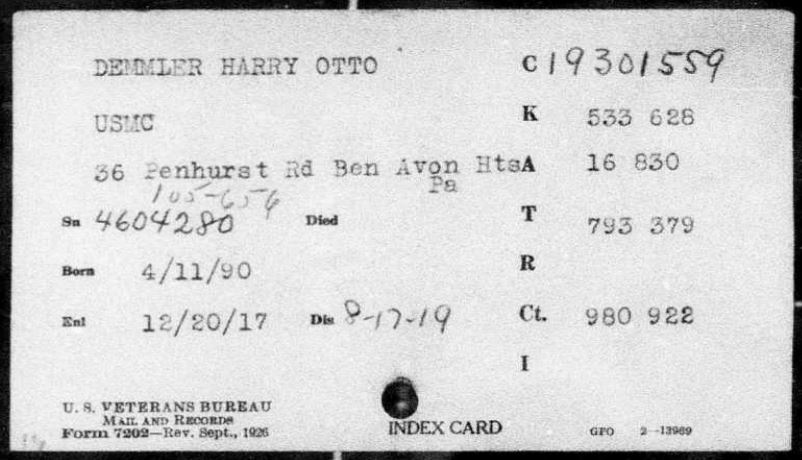

Harry O. Demmler, age 27, a clerk for the Manchester Realty Company in 1917, did not answer the exemption question at all on his draft card. He enlisted in the Marine Corps in December 1917, trained at Parris Island, SC, and would later participate in one of the Marine Corps most brutal campaigns to take place near the end of the war, the crossing the Meuse River. Harry Demmler served as a Sergeant in the 5th Marines, 43rd Company, survived the crossing, and was part of the occupation of Germany. He was later promoted to Gunnery Sergeant before returning to the United States.

Oscar W. Demmler, age 25, was a public school teacher at the time of the draft. Like his brother Fred, he too claimed exemption based on “Consciention,” but was still required to serve, and did so for 10 months overseas during the war. He was spared any direct involvement in hostile engagements.

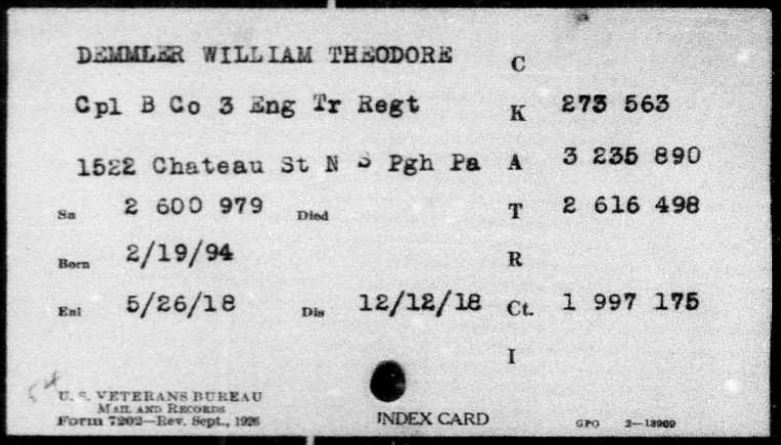

And finally, William T. Demmler, age 23, was working as a clerk in his father’s business. He also answered the exemption on the draft cards as “Conscientiously opposed.” He was not required to go overseas during the war, but he did serve in an Engineering Training Regiment in Virginia for about seven months.

Fred Demmler, along with his 136th Machine Gun Battalion, left Newport News, VA on June 22, 1918, aboard the troop transport Caserta headed for France. During the first phase of the Meuse Argonne battle, Demmler was hit in the shoulder and arm with shrapnel. Price wrote that his brother later learned that “He [Fred] picked out the pieces of shrapnel himself and had the doctor bandage him. After which he went about his work as usual.” The evidence of admiration is clear in Price’s writings, illustrating how well respected he was among the men of his unit. An example of his positive attitude was expressed by one of his fellow soldiers, “He never said a harsh word. He was always cheerful and never kicked. When we complained about the feed or anything, he said it would be better later.” When asked if Fred had a particular ‘buddy’ in the unit, one of the sergeants responded, “No. He was everybody’s friend.”

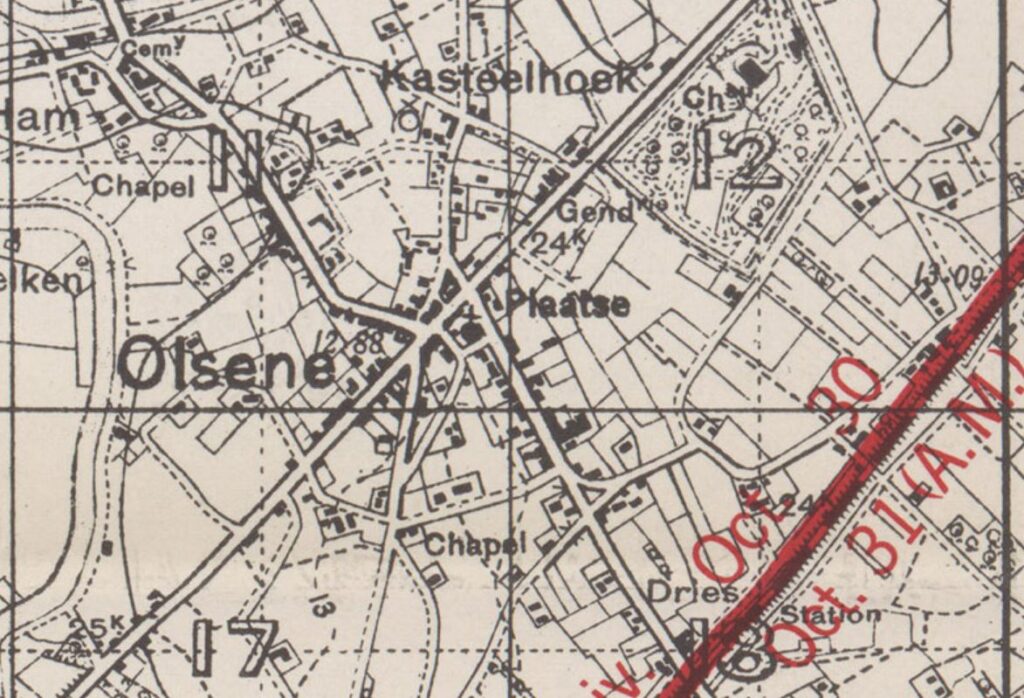

On the night of October 30-31, 1918, the 37th Division relieved the French 132nd Division on the front line south east of Olsene, Belgium. An operation was ordered to be launched on the morning of October 31, 1918 with the Escaut (Scheldt) River to the north as the final objective. The 37th Division, in which the 136th Machine Gun Battalion was attached, would attack the Germans with the French 128th Division to the right, and the French 12th Division to the left. The Germans started a general withdrawal on November 1 with the 37th Division following in pursuit. The following incident was provided by the historian of the 136th Machine Gun Battalion:

“Our company went ‘over the top’ on the morning of 31 October, near the Château de Olsene [see the “Chau” above the No. 12 in the top left quadrant of the map], from positions along the railroad tracks about 900 meters from the enemy front line. The advance was begun under a rolling barrage furnished by the French guns in support. Sergeant Demmler commanded a squad of the First Platoon whose guns were in support. Promptly at 5:30 the advanced was begun. The Platoon had a little more than cleared the railroad when they were caught in the German counter barrage, shells falling everywhere, and making any attempt at taking cover worse than useless [see photo of the area below]. About 75 meters beyond the tracks, Sergeant Demmler was struck by pieces of an exploding H.E. [high explosives] that fell in the midst of the squad he lead. Corporals Leo A. Damicon and Felix L. Marlett stopped and offered aid and assistance to a place where medical attention could be had, but to each his answer was the same, “Keep on with the advance, they need everyone of you up ahead.” Sergeant Demmler was found by runners returning to the Company and carried to the Olsene dressing station. Three days later he died in the hospital. The splendid record of this brave soldier has won the admiration of all who knew him.”

On November 2, 1918, Fred Demmler died of his wounds in Hospital No. 5 in Staden, Belgium and was buried the next day in a temporary gave. On June 5, 1919, he was disinterred and reburied in the American military cemetery in Waregem, Belgium. At the request of his family, his remains were returned to the United States and were received by his family on May 12, 1919. The funeral service was held in the Smithfield Cemetery in Homewood under a tent erected by the pastor of Saint Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church where Demmler was a member. His six brothers served as pallbearers for their fallen brother.

Photo credit: Pittsburgh Post-Gazette; Source: Facebook community @FredADemmler

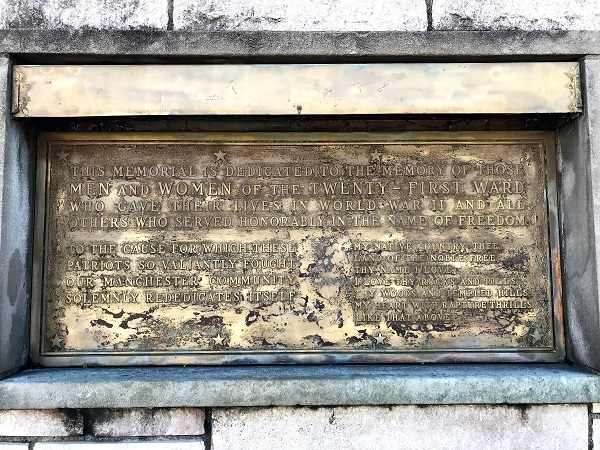

About 1925, Edward & Minnie Demmler sold their home in Manchester and relocated to the Ben Avon neighborhood of Pittsburgh. Their home at 1522 Chateau soon became the Manchester Educational Center where meetings and lectures could be held, but also a place for young artists in the community to come an create art and drama. In 1944, Samuel Ely Eliot, the cousin of poet T.S. Eliot, was Executive Director of the Manchester Center and chaired a committee to have a memorial plaque installed at the corner of Chateau and North Franklin that reads in part, “Dedicated to the memory of those all men and women of the Twenty-first Ward who gave their lives in World War II and all others who served honorably in the name of freedom.”

Why have I detained you for a tale so plain? What was he but an obscure young painter, thirty years old, with his way to make? Why should I point him out to you among the millions?

Because he was my friend? No. Because he is yours. Because I thought I saw in him the seeds of greatness? No. Because the seeds of greatness which were in him are in you; and he shall make you see them. I give him to you young men to be your friend, loyal and high minded. I give him to you young women to be your lover, clean of body and of soul. He will be worthy of your friendship and of your love, and you shall be worthy of his in return.

He is to be immortal. And it is you who must make him so. Let him kindle in your hearts a fire which will not go out. He that would have made great canvases glow with the might of his spirit and the splendor of his imagination shall not now live by art alone, but by the living deeds of you. You shall be his masterpieces. You, immortal youth, shall be his immortality.”

Lucien Price Immortal Youth: A Study in the Will to Create