Ask any Marine to name a battle from World War I and you will undoubtedly hear “Belleau Woods” recited as an answer. Taught to every new recruit and officer candidate, it was the fighting spirit in the ranks of those men that has become an enduring symbol for the United States Marine Corps. It may also be the lore of this battle that continues to draw historians to study the Battle of Aisne (Belleau Woods) that took place over a century ago.

As a former Marine, I can certainly be accused of perpetuating the lore by reciting the quote by Captain Lloyd Williams, “Retreat, hell! We just got here.” But even growing up on my childhood street of “Belleau Woods Boulevard,” I don’t have the back story on so many of the men who fought in this battle. Author Edward Lengel may have said it best, “the names of the men who broke through the main German positions on June 11, 1918 and turned the tide of the battle are lost to posterity.” While this may be true, I hope to make an effort of honoring these men by learning some of their names.

So, it should be no surprise that this article will highlight at least one Pittsburgher who was leading head-on into this historic fight, but sadly, also became one of the first officers to be killed at the start. Admittedly, I had never heard the name of this particular Marine from Pittsburgh until doing research for my article “Poet of the Future.” In short, I wrote about two friends from Pittsburgh that met one evening in July 1918 during the war. Corporal Francis Hogan offered Lieutenant Hervey Allen the address of a mutual friend whom they both knew from Pittsburgh. This mutual friend, Lieutenant William Dabney Frazier, was attached with the Marines but had already been killed when the two met that evening. Allen could not bring himself to telling Hogan the news of Frazier’s death.

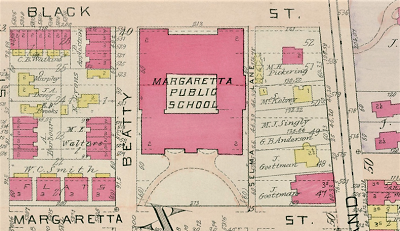

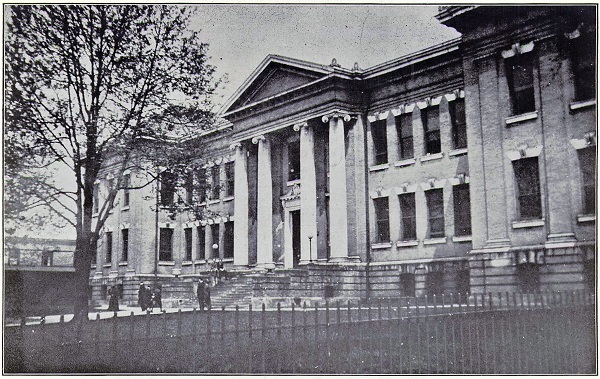

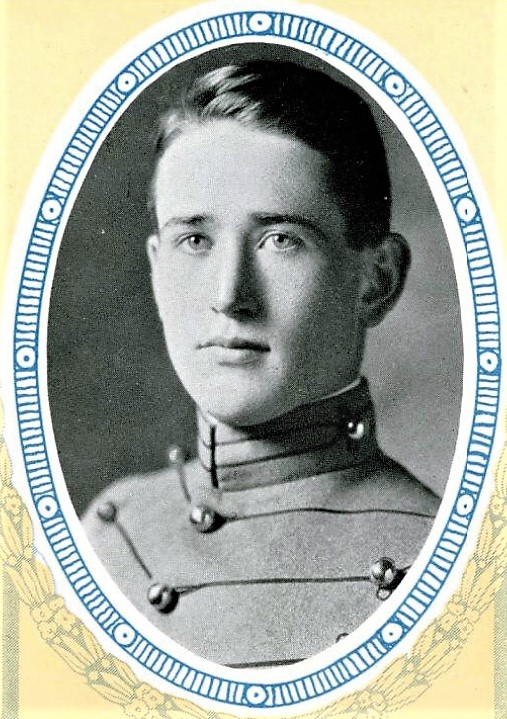

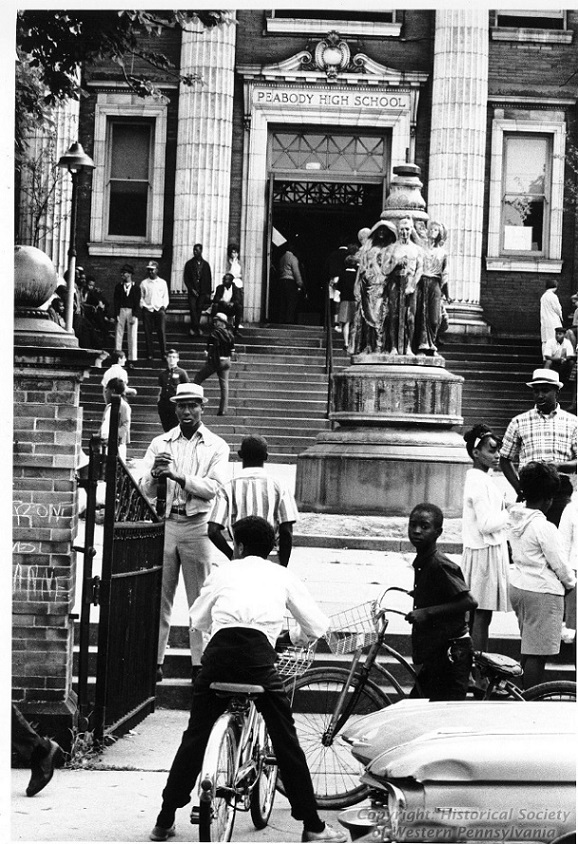

William Dabney “Dabs” Frazier, born in Pittsburgh on December 28, 1896, likely met Francis Hogan at the Margaretta Street school in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh. This school building was later expanded and renamed the Peabody High School. Hogan graduated from Peabody in 1916, but his friend “Dabs” spent the last two years of high school at Culver Military Academy, a college preparatory boarding school in Culver, Indiana. Frazier had aspirations for a military career, hoping to attend West Point after high school. He was a member of the Culver football and basketball teams, and a member of their athletics council.

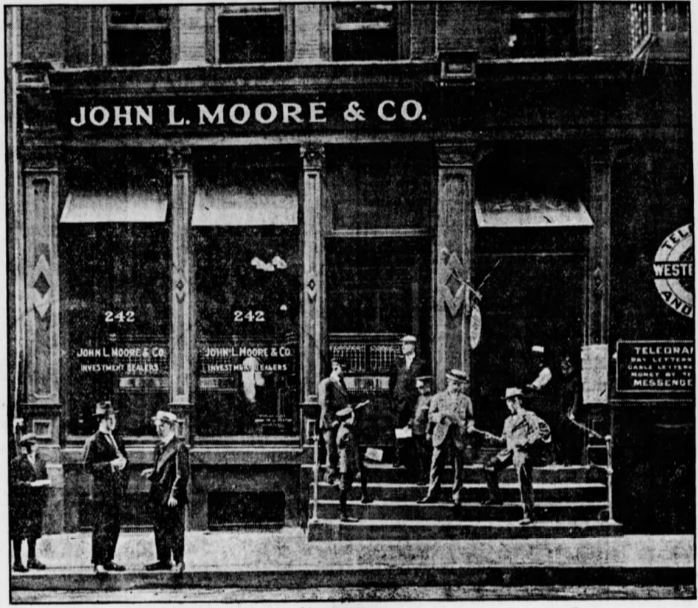

Following his June 1916 graduation, “Dabs” returned home to Pittsburgh where he lived with his father Walter A. Frazier and Mable Dabney Frazer at 5744 Ellsworth Ave in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh. When Frazier returned, he would have been walking into a household under great distress as a result of his father’s professional career being turned on its head. Walter A. Frazier was the manager of the John L. Moore & Company Investment Dealers, a brokerage house that managed the investments of the Amber Oil & Refining Company. The same month the young Frazier was graduating from Culver, John L. Moore was being charged with embezzlement, and by November 1916, both John L. Moore and Walter A. Frazier pled guilty before the United States district court to mail fraud, later sentenced to a $1,000 fine and three months in the Allegheny County jail.

It’s unclear exactly how these events played out for the young Frazier, or how he reacted to his father’s legal affairs, but we do know that he left Pittsburgh against his parents’ wishes, traveled to Toronto, Canada, and enlisted in the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Forces. On January 25, 1917, Frazier signed an oath of allegiance to King George the Fifth and agreed to serve for at least one year during the war between Great Britain and Germany. The United States had not yet entered into the Great War, and the 20-year-old Frazier was now in Canada attached to the 208th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Forces.

The following month, Walter A. Frazier contacted the British Consulate in Pittsburgh to get his son discharged from the Canadian unit on the grounds that he was still a minor and an American citizen. While the young Frazier reported 1895 as his year of birth on the enlistment papers, his father provided a copy of a Pittsburgh birth certificate showing the correct year as 1896. The father also provided a statement that read in part that his son “mysteriously disappeared from home and we knew nothing of his whereabouts until informed by through the American Consular Service of Ottawa, Canada, that he had enlisted in the 208th Overseas Battalion of the British Army. He left home against the wishes of his parents, his enlistment in the American or any other armies having been expressly forbidden by myself and his mother.”

On March 24, 1917, the young Frazier was discharged from the Canadian forces after only a few months. Shortly after his return to the United States, Frazier enlisted in the United States Marine Corps on July 6, 1917, exactly three months from the date that the United States officially declared war on Germany. No one can fault the Frazier parents for wanting to keep their only child safe. However, we do know that Frazier had been preparing for the opportunity to serve in the military since he was a young boy, participating in local youth organizations like the Highland Cadets, and the United Boys’ Brigade of America, places where he would first begin to learn the skills of drill and discipline. He was now out of high school, the country was at war, and regardless of what was happening in his family’s personal life, Frazier was ready to serve.

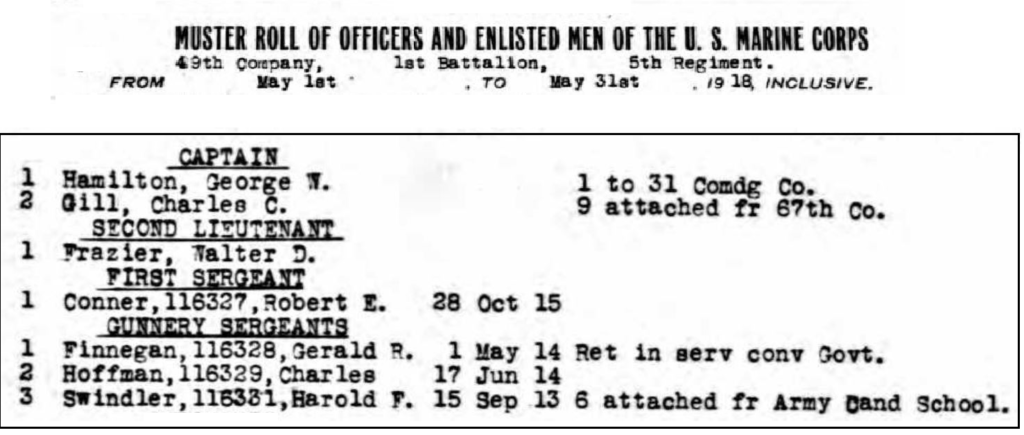

When I see one of the early Marine Corps recruiting posters, First to Fight, I will now think of this young man from Pittsburgh. He was sent to Marine Officers’ Training Camp, Marine Barracks, Quantico, Virginia, and was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant on August 27, 1917. Following his initial training, he was placed under the command of Captain George W. Hamilton, 49th Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment for service in France.

This is a small clipping of the muster roll that shows some of the names recorded just prior to the June 1918 battle. Take note of a couple of the Marines who served with Frazier. Captain George W. Hamilton led the 49th Company, earning the Distinguished Service Cross and Navy Cross. Gunnery Sergeant Charles F. Hoffman (born Ernest August Janson), was the first Marine to be awarded the Medal of Honor during WW1. WW1 4th Brigade (Marine), 2nd Division, AEF and WW1 AEF Historian and Battlefield Guide Steven Girard records Hoffman’s awards as Medal of Honor (both Army & Navy), Silver Star Medal (1st, & 2nd Award), Purple Heart Medal, French Médaille Militaire, French Croix de Guerre with Palm, Italian Croce al Merito di Guerra (War Merit Cross), Portuguese Medalha da Cruz de Guerra (War Cross), and the Montenegrin Silver Bravery Medal for his actions against the enemy serving with the Marines during the Battle of the Aisne (Belleau Wood).

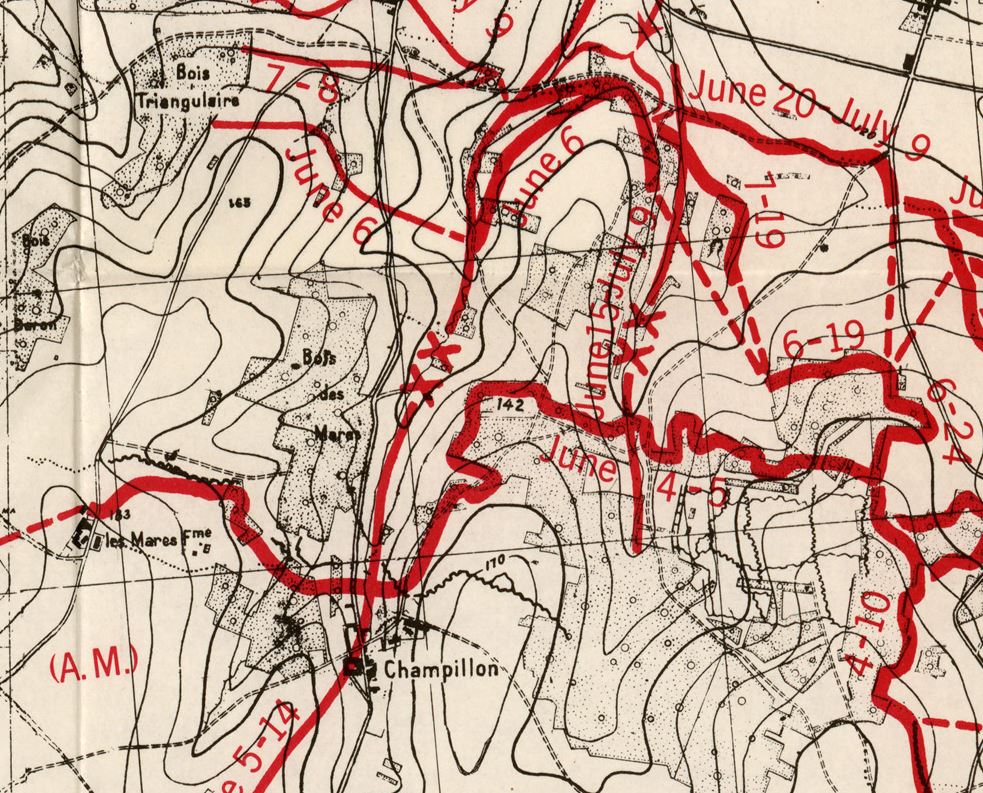

In my eyes, Frazier epitomizes how the Marines are portrayed on that recruiting poster, First to Fight, as he was placed on the cusp of one of the Marine Corps most epic battles, and as a leader of Marines, he was out front, positioning his platoon for an assault on enemy positions near Hill 142, just north of Champillon. It is likely that Fraizer’s actual date of death was June 5, 1918, as he was waiting for orders rumored to have his platoon attack the next day. Some records show his date of death as June 5, while others June 6.

Major Gary Cozzens (USMCR) describes “the capture of Hill 142 as a defining moment in the annals of Marine Corps History.” The terrain (see 1919 Signal Corps photo above) that Frazier was crossing consisted of alternating patches of grain fields and woods, defended by Germans who were placed into positions to confront the approaching troops. This post will not go into the detail of the battle, but I encourage you to read Cozzen’s article “How Will the Americans Behave in a Pitched Battle?” published in the Winter 2018 issue of Marine Corps History where he provides the story of those events, as well as a list of men receiving valor awards for their actions. History shows that 2nd Lieutenant Walter Dabney Frazier was posthumously awarded three of the Nation’s highest military awards for valor, the Distinguished Service Cross, Navy Cross, and the Silver Star, attesting to “the supreme proof of his extraordinary heroism.” Frazier was also awarded the Purple Heart and French Croix de Guerre with Bronze Star.

I am also grateful to Author Kevin C. Seldon, sharing firsthand accounts of his research about Lieutenant Frazier, along with another Marine from Western PA who was with Frazier near Hill 142. Seldon’s book, Among the Ranks of the Carrion Men, gives a glimpse at the graphic details of the horrors of war. Taken from Frazier’s burial file, Seldon provides us with a vivid description of death: “Before anyone could react, the momentary ear-splitting scream of an incoming shell erupted into a blinding flash amidst Frazier’s gathered platoon. A large shell fragment killed Frazier instantly as it struck him in the middle back and passed entirely through his kidney. Deadly shards of steel from the same round tore into several other members of the platoon including 23-year-old Private James Sherman Schall, a carpenter from Armstrong, Pennsylvania. A fragment struck Schall in the face with such force it shattered most of his skull as well as facial bones and blew his lower jaw off killing him instantly.”

I believe we must have these blunt descriptions to remind us of the pure hell faced by these men. It also reminds me to ponder the anguish of the Marine who survived that day, the carnage he witnessed, and the fact that he had to recount the details recorded above. We can only hope that many of the families who lost their sons were spared these vivid details we read today.

Thanks to the work of historian Weldon Hoppe, we now have quick access to search the details on the burial cards for over 78,000 American soldiers in World War I. The information gathered on these burial cards gives us the initial burial location for both Frazier and Schall, but Hoppe’s website also provides quick access to locating others who were buried in that same cemetery. In this case, we know that both men were initially buried in a French civilian cemetery near Bézu-le-Guéry. Again, using a resource developed by Hoppe, we can quickly access the location of this cemetery through his AEF Resources Map.

Shortly after the war, the United States government gave the families of the fallen an option on where their deceased could be buried. The remains of Private Schall, at the request of his father, were returned to the United States and were buried next to the Marine’s mother in Cochran Cemetery, Templeton, PA. The Frazier family also requested the remains of their son be brought back to the United States, and Frazier’s body was interred in Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, VA on July 28, 1921.

In 1923, the Peabody High School World War Memorial was completed by Frank Vittor, a tribute made possible through the donations of students, faculty, and the general public. The memorial was dedicated during a ceremony on May 30, 1924, and included the names of 17 former Peabody students that died during the war. Frazier’s name, along with his former classmate Francis Hogan, were counted among the dead. Mrs. Mable Frazier, along with five other Gold Star Mothers, unveiled the memorial to the public at the ceremony that day. This war memorial is currently located on the grounds of the Obama Academy in East Liberty and also includes the names of 532 graduates and former students who “offered their all to their country during the World War.” There is presently an effort to refurbish this memorial through Preservation Pittsburgh, and your donation, regardless of the amount, would be greatly appreciated by the organizers.

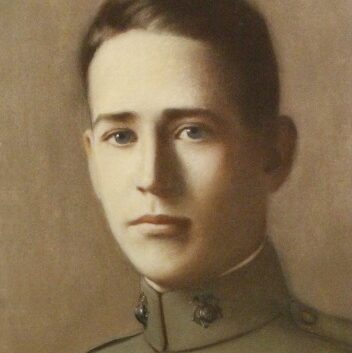

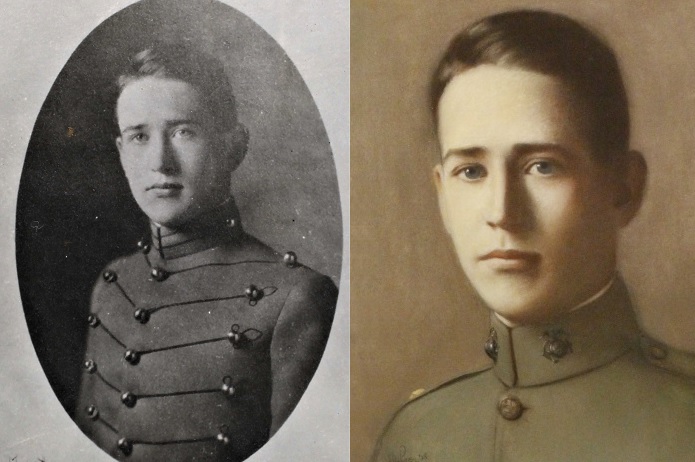

In the Spring of 1925, commissioned by the Culver Military Academy, artist Hue Poe began work on creating pastel portraits of men from the academy who lost their lives during the war. Using photographs from the days the men attended Culver, Poe created portraits of each deceased wearing the uniform of the branch in which they served. The portrait of Frazier is shown here with the Marine Corps eagle, globe, and anchor collar insignia, as well as his 2nd Lieutenant bar on his shoulder.

Story by Andrew Capets