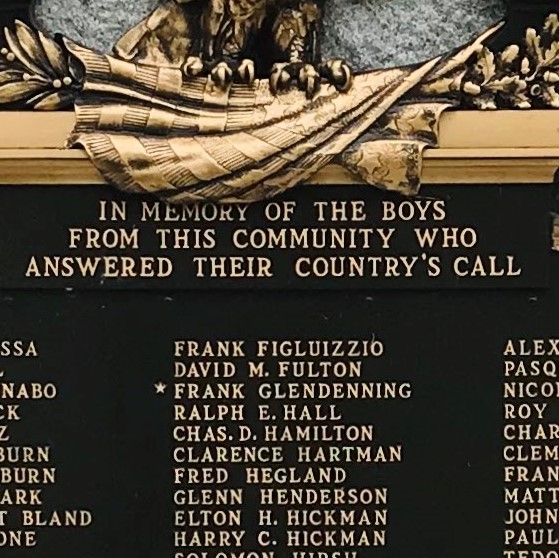

One of the interesting curiosities of researching the Great War, when focusing on it from a Pittsburgh perspective, has been the seemingly coincidental relationships among the many people being studied. A few years back I was watching a video lecture given by historian and author Edward Lengel discussing his book To Conquer Hell. He recommended a book written in 1926 by William Hervey Allen Jr called Toward the Flame; A Memoir of World War I. As I was reading Allen’s book, one of the key subjects written about in his story was a person whom I was familiar with from my local historical society research, Lieutenant Frank Glendenning, a soldier from my hometown of Trafford, Pennsylvania. I knew a little bit about Glendenning because his name appears on our local WW1 memorial, and our group of volunteers in Trafford had recently honored Glendenning during a memorial park renovation project. Suddenly, Allen’s story had a heightened interest and I had a difficult time putting this book down. Despite already knowing how the story ended for Glendenning, I was drawn into Allen’s writings, learning more details about the war through this local connection.

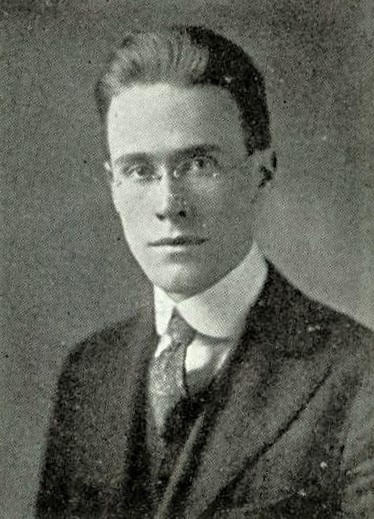

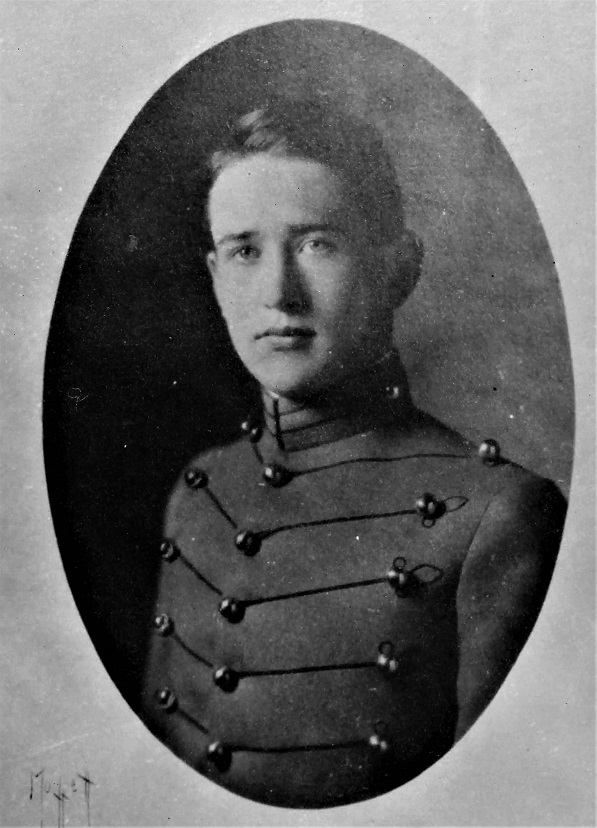

There was one particular incident in Allen’s book that I wish to highlight here because he writes about four men from Pittsburgh within just a few pages of his chapter titled “The March to Château-Thierry.” The chapter discusses an event that took place in July 1918, just outside of Château-Thierry, where Allen, serving with the 111th Infantry, (28th Division) learns that he is located near the 4th Infantry (3rd Division), and the unit in which his good friend Francis Fowler Hogan from Pittsburgh was a member. Allen was hoping to be able to locate this regiment, and in particular, meet up with his friend. Hogan and Allen likely knew each other from the times they sang together in their church choir, Allen being seven years older. Hogan was still a junior in high school when Allen received his bachelor’s degree from the University of Pittsburgh in 1915.

ALLEN

HOGAN

GLENDENNING

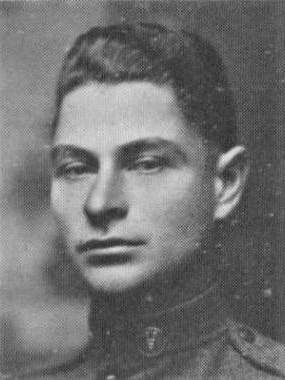

Francis Fowler Hogan was born in Pittsburgh on November 13, 1896, to Thomas and Emma Hogan who once lived in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh. The family home at 730 N Euclid no longer exists; only an empty lot remains today. Thomas Hogan was a tea and coffee dealer in Pittsburgh and died in Saint Francis Hospital of pneumonia just one day before Francis Hogan turned eleven.

Hogan attended Peabody High School where he took part in the debate team, drama club, and the literary society. In May 1916, he took part in the Oscar Wilde class play titled, “Importance Of Being Earnest,” and a classmate commented on his performance stating, “Mr. Hogan as Algernon Moncrieff was his own charming self to the delight of his audience.” Hogan was also editor of the student newspaper, The Melting Pot, and graduated high school in 1916 with honors. Following graduation, he entered the newly formed School of Drama at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (present-day Carnegie Mellon University).

On April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany, and within two months, Hogan enlisted in the National Army. He was first sent to Camp Colt in Gettysburg PA, then to Camp Greene, NC, and finally to Camp Stuart, VA, a troop clearinghouse during the war. He boarded the troop transport “Great Northern” exactly one year to the date that the United States declared war. Hogan was assigned to Company M, 4th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Division, and would take part in three major military operations, Aisne-Marne, Saint-Mihiel, and the Meuse-Argonne.

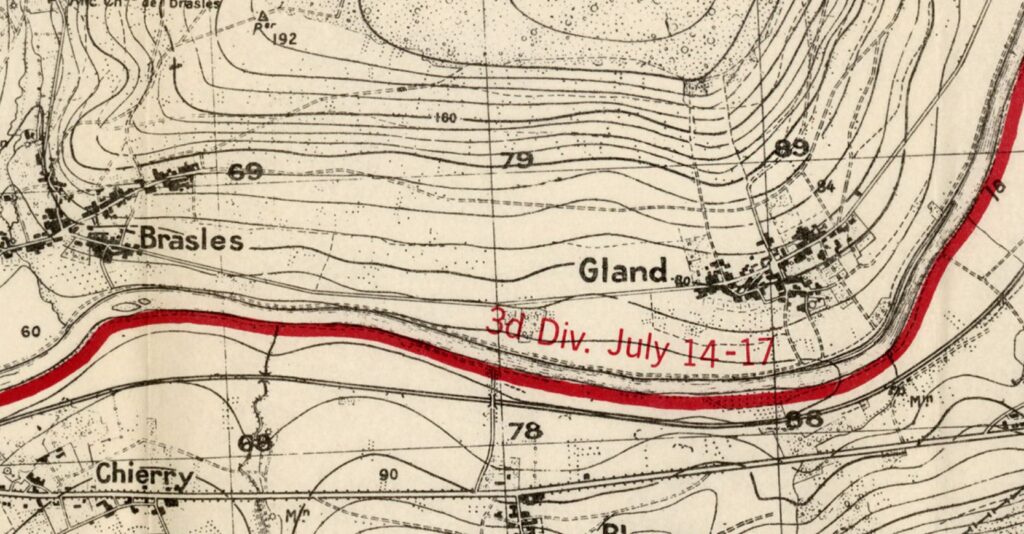

One evening during the Aisne-Marne Offensive, Allen was given an order from General William Weigel to deliver a message to the commanding officer of the 4th Infantry, Colonel Halstead Dorey, to provide the colonel with troop locations and front-line positions of the other units in the vicinity. Allen took one officer with him to complete this liaison, choosing Lieutenant Frank Glendenning. Allen provides a fascinating account of trekking across this worn-torn part of France with Glendenning in order to deliver the message to the colonel who then held his command post in the ruins of a 15th-century church in Gland. This church was destroyed by the Germans in 1918. A new church was rebuilt across the street from these ruins in 1919. Upon delivering the message, Allen asked the colonel where he might find Company M; the unit was situated directly across the street from the church.

Allen was able to locate Hogan and they could visit with each other for only about ten minutes. There is a heartening exchange between these two friends when Hogan wants to share the address of a mutual friend from Pittsburgh, William Dabney Frazier, whom they “had known in happy times.” Allen was given the address by Hogan, but Allen makes a decision to withhold the fact that he already knows that Frazier was dead. Lieutenant Frazier was killed in action while he was serving with the 5th Marine Regiment during the Chateau-Thierry Offensive. It must have been trying for Allen to spare his friend Hogan from the immediate grief of Frazier’s demise, Allen writing, “We seemed too close to it all then.”

We know that Hogan did learn about his friend Frazier’s death during the war as he wrote home to his mother on July 31, 1918, telling her about the brief meeting with Allen. “One night on the Marne, while the great second battle was on, I met a friend. We had only a few minutes together, but I managed to give him the address of a friend of both of us whom I had just heard from. He was a fine chap, the absent friend, and I had known him when we flew our kites in Highland Park. I was badly hit when I learned he had been killed.” Hogan also learned that Allen withheld the information about Frazier’s death when they were together that night in Gland, Hogan writing, “The other day I received a letter from the fellow I had met on the Marne [Hervey Allen]. He was in hospital. He wrote: ‘Dab’s snuffing out is bad. I knew it the night I talked to you, but couldn’t say anything to you when you gave me his address.’

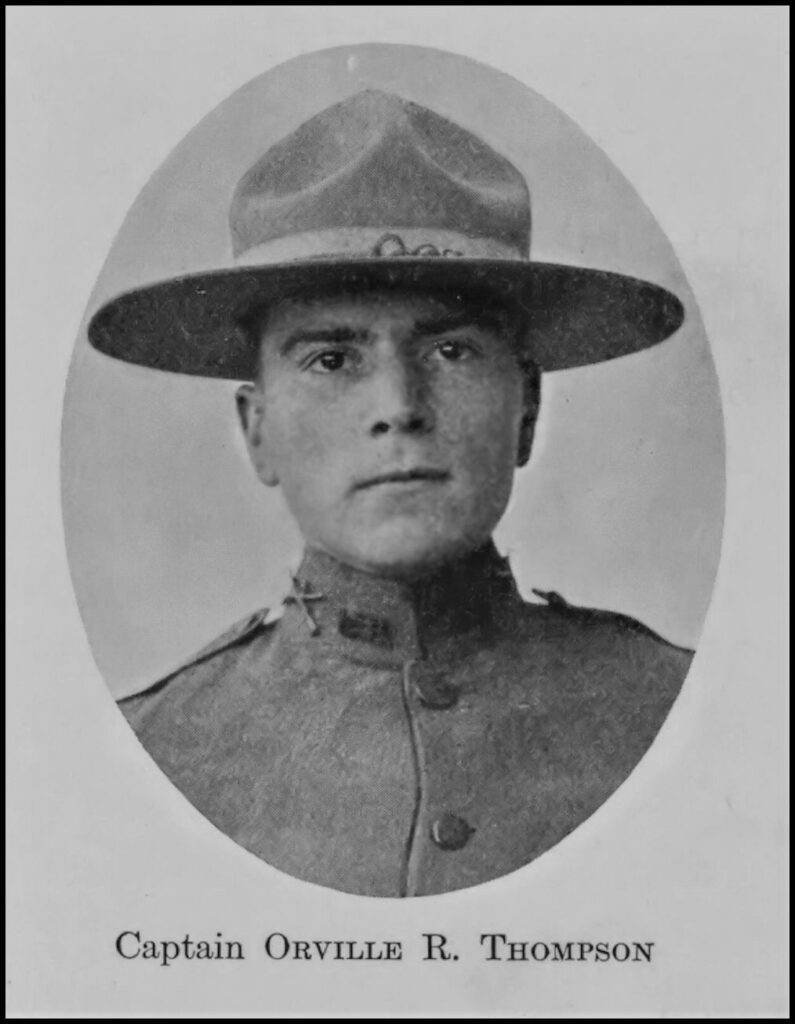

Allen and Glendenning left Hogan just as another round of German shelling began, and so they started back to their own regimental command post. Dodging the shells along the way, they made it back to report the situation to General Weigel. Upon entering the village of Brasles, Allen met up with another Pittsburgher, Captain Orville Thompson, who was “watching the result of the shelling rather anxiously.”

The following month, both Capt. Thompson and Lt. Glendenning would lose their lives in the Battle for Fismette. Allen was wounded during this campaign and had to be evacuated to a field hospital to recover. These injuries kept him out of the next major battle, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

FRAZIER

THOMPSON

During the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the 3rd Division received field orders that directed Hogan and his 4th Infantry to be place in the new offensive, battling to clear the Germans from the Cunel Heights. During the evening of October 16-17, 1918, orders directed the 3rd Division to mop up Bois de Forêt and Clairs Chênes woods, and consolidate all ground gained to the north. It was during this period of fighting that Corporal Francis Hogan was killed.

The total strength of the 4th Infantry during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive on September 30th was 3,662 men. Following the hostilities in October, this strength was nearly cut in half in just one month, leaving only 1,843 men remaining. The casualty numbers for the 4th Infantry for the dates of October 14-27 record 414 men wounded, 37 died of wounds, and 143 killed in action, of which Francis Hogan would be counted.

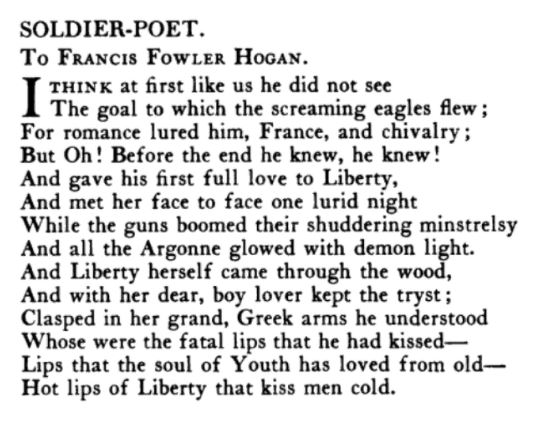

I’ve thought about that one night in Gland as recalled by Allen, and wonder how he processed losing so many friends in a few months time, and in particular, his friend Hogan. I don’t doubt that writing about his experiences at war was a method of coping with his grief. He took quite a risk to seek out his friend, even for just a few minutes of conversation. In 1921, Allen published a book of poetry and dedicated the book to his friend, including the poem “Fulfilled” written by Hogan while aboard his troop transport heading to France. Hogan’s poem was so well received at the time that his work was included in the publication The Poets of the Future – A College Anthology for 1917-1918.

After Hogan was killed, his remains were initially buried in a temporary gravesite in Cunel. On April 19, 1919, his remains were disinterred and reburied in the Meuse-Argonne American cemetery in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon. At the request of his mother, Corporal Hogan’s remains were disinterred and shipped back to the United States where they were received by the H. Samson Funeral Home on Sixth Avenue, Pittsburgh on August 11, 1921. Services were held at the Samson chapel on Saturday, August 13, with Hogan’s final resting place in the Homewood Cemetery, Pittsburgh.

The following is believed to have been last poem ever written by Hogan titled “The Adventure.” It was included in a letter received by his mother and shared with the Pittsburgh Dispatch in November 1918.

I have found a cave.

Dark and very deep;

Who may know what wanders

In the cannon sleep?Maybe there are gems

And a heap of gold;

Maybe sacred volumes

Stored there of old.Maybe there are poppies

Which the gnomes hoard;

Bit of dragon skin,

Or a broken sword.Or a queen enchanted

Francis Fowler Hogan

Whom we may free;

Maybe only death –

Come, let us see.