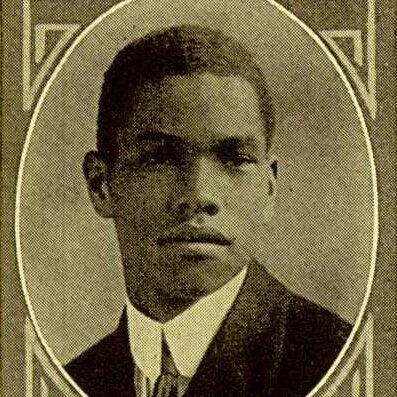

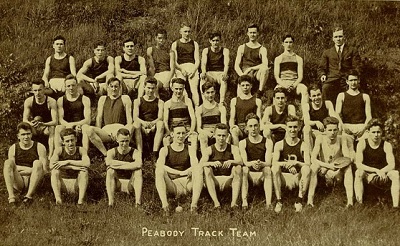

While researching the history of Francis Hogan for Poet of the Future, an article about a Pittsburgher killed in action during the Great War, I happened upon a man who graduated from Peabody High School the year prior to Hogan’s graduation. The photo of a young man caught my attention as I browsed the 1915 Peabody yearbook looking for other references to Hogan. This young man was John Fountain Barnette Jr, and he stood out as being the only African American man pictured in a couple of school track team photos and was the only African American male to graduate from Peabody High School that year. While I did not examine the demographic makeup of Pittsburgh during that period, I did learn that school enrollment during that era was not at all like we know it today. During Barnette’s school years, not all Pittsburgh youth were afforded the opportunity to attend high school. An entrance exam was required to be taken, and only a limited number of admissions were granted by the Pittsburgh Central Board of Education during this period. In 1904, Pittsburgh was still primarily an industrial community with only 2,105 students attending high school, but by the time Barnette graduated in 1915, Pittsburgh’s high school enrollment had grown to 6,008 students.1

Already having a basic knowledge of the segregation that occurred in the U.S. military during the war, I was curious to know if Barnette served in the Great War. I confirmed that he indeed served and was drafted into the Army at age 24; however, Barnette unquestionably had a military experience very different from that of his former classmates. For anyone unfamiliar with the topic of military segregation, it should be noted that from the very start of Barnette’s induction, the color of his skin dictated how he was treated and where he would serve. Institutional racism existed in the military, and only a small number of black officers were given the opportunity to lead troops at that time. Plain and simple, Barnette was asked to support the fight for democracy, but not afforded equal treatment as a soldier in uniform. The topic of segregation is far more in-depth than what will be explored in this article, but it is important to acknowledge the tragic conditions under which he served.

Perhaps it was my basic understanding of these facts while flipping through the pages of the Peabody high school yearbook, that I took an interest in exploring the background of Barnette. My goal here was simply to research his background and honor his service as a Pittsburgher serving in the Great War. John Fountain Barnette Jr was the youngest of three children, born in Lynchburg, Virginia in 1893. He was 21-years-old when he graduated from Peabody High School in 1915. Barnette was a senior when Francis Hogan was a junior, and the two would have undoubtedly known each other. Barnette was a member of the “Dramatic Club” and Hogan served as one of the club officers that year. Barnette was also a member of the Peabody track team and took first place in the 440-yard dash, as well as contributing to the team championship for Peabody at the Washington and Jefferson track meet held in May 1915, where fifteen schools from Western Pennsylvania, Eastern Ohio, and Northern West Virginia competed.

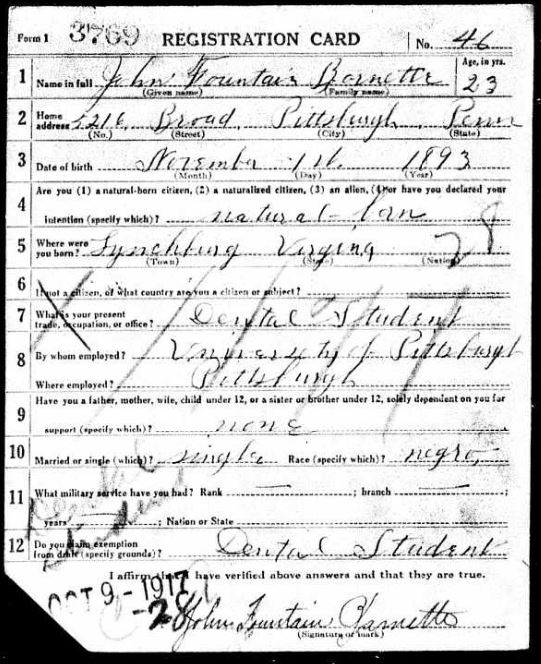

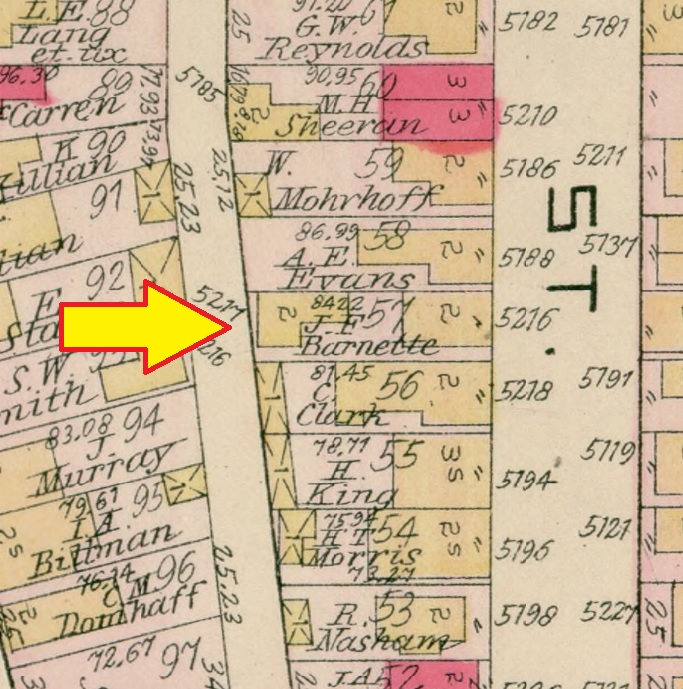

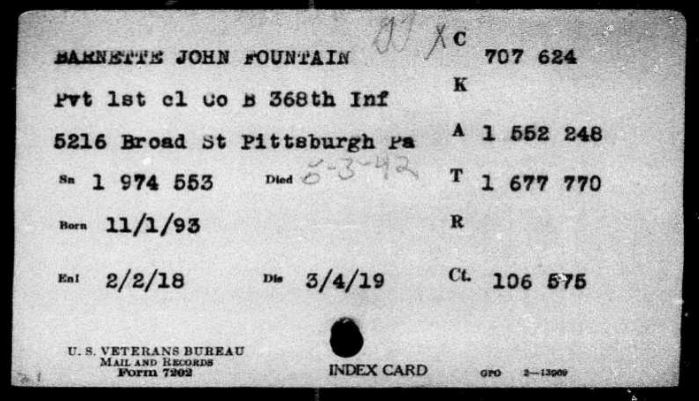

Barnett attended the University of Pittsburgh to study medicine following high school and was also a member of the Pitt Track and Field team. His draft card, signed in June 1917, indicated that he was a dental student living at 5216 Broad Street in the Garfield neighborhood of Pittsburgh. He was then living with his parents, John F Barnette Sr and Mary Merchant Barnett.

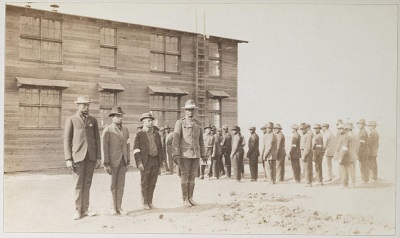

Barnette was inducted into the Army on February 2, 1918, and assigned to the 325th Field Signal Battalion, 92nd Division, organized at Camp Sherman in Chillicothe, Ohio. The 92nd Division, nicknamed the “Buffalo Soldiers,” was one of two segregated Army divisions formed during the war, the other being the 93rd Infantry Division, nicknamed the “Blue Helmet” Division.

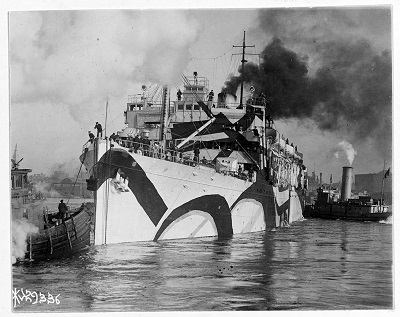

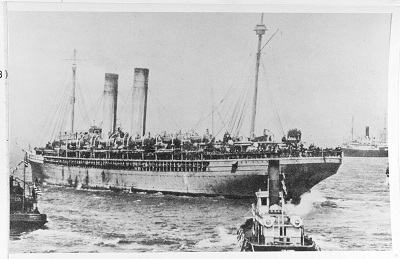

With Barnette attached to a field signal corps unit, he would have been trained on communications between front-line units and division headquarter units using telephone, radio, and aerial mapping, but he may have also learned communications using carrier pigeons or semaphore flags. Just a little over two months after Barnette arrived at Camp Sherman, his father John F Barnette Sr passed away in Pittsburgh at the age of 55. The young Barnette would have completed his initial training at Camp Sherman and then traveled to Hoboken, New Jersey, to set sail for France on June 10, 1918, aboard the troop transport Orizaba. Upon arrival in France, his battalion proceeded to the Bourbbonne-les-Baines training area, and on August 12, they moved near Bruyères in the Vosges Mountains to be affiliated with the French 87th Division for participation in the Saint-Dié Sector.

Camp Sherman accepting new recruits.

Troop transport Orizaba

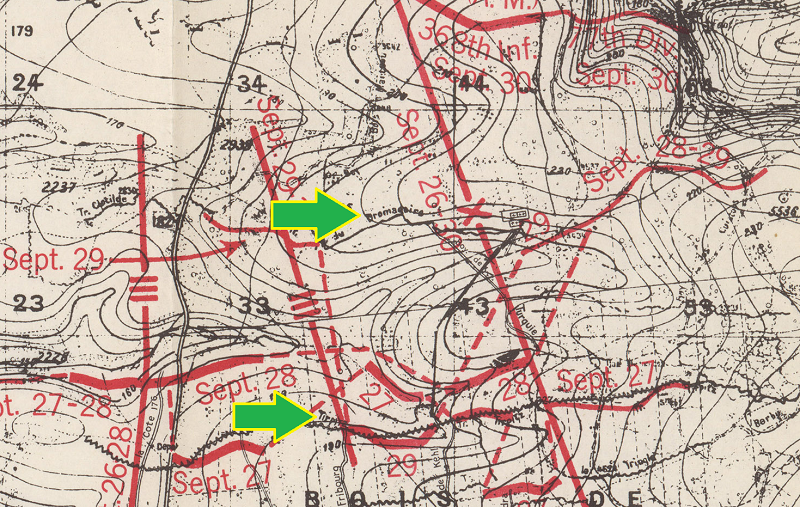

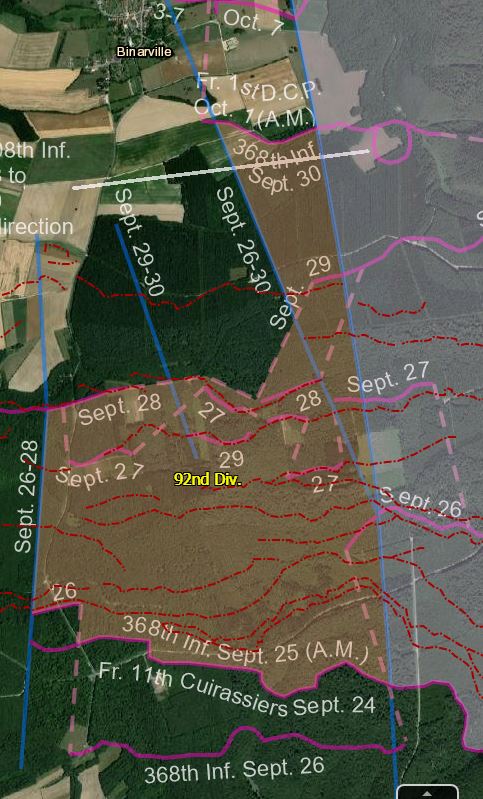

Less than two weeks before the start of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, Barnette was transferred into the 368th Infantry Regiment, Company B. This transfer into a combat infantry unit put Barnette directly into the frontlines for the start of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, and right on the edge of the Argonne Forest. This formidable terrain was heavily wooded with well-built trenches and dugouts constructed during the four years the Germans had occupied this region. On the morning of September 26, 1918, the 92nd Division started their advance with little to no artillery preparation to assist in destroying the fortified wire entanglements in front of the advancing American regiments.

On September 30, 1918, Barnette, attached with Company B, took part in the French assault aimed at taking back the German-occupied village of Binarville. His battalion advanced at 11 AM, moving through the old trenches of Tranchee Tripitz and Tranchee to Du Dromadaire. Working alongside the French troops, Companies B and C received heavy shelling upon entering Binardville, causing them to pull back to positions about 300 meters south of the village. It wasn’t until 4 PM that afternoon that Companies A, B, and C entered Binardville, and were ordered to hold their occupied positions.

The 368th Infantry did not withdraw from the frontlines until the early hours of October 1st and were ordered to move to Tranchee de Damas. Barnette survived his days of combat in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, but several members of his 368th Infantry did not fare as well; 226 wounded, 42 killed in action, and 16 died of wounds received.

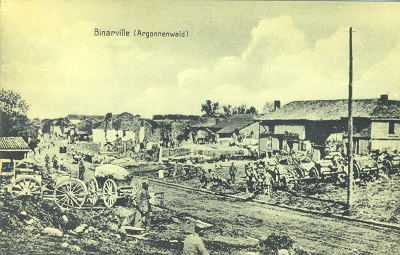

Binardville destroyed by shelling.

Binardville occupied by Germans.

Following the Meuse Argonne Offensive, the 92nd Division participated in the Marbache Sector and Woevre Plain Operation from October 8, 1918, until the end of the war on November 11, 1918. During this period, the 368th Infantry Regiment recorded nine wounded and no deaths. They departed France on February 5, 1919, aboard the troopship Harrisburg, and arrived in New York on February 15, 1919. Barnette was honorably discharged from the Army on April 4, 1919.

Troop transport Harrisburg

Barnette returned home to live with his mother, but it does not appear that he returned to the University of Pittsburgh to pursue his medical degree. The 1920 U.S. Census listed his occupation as a waiter, and in 1930, he was married and working as a clerk in a bond house. In April 1924, just one month before the dedication of the Peabody World War Memorial, where John Barnette’s name has been memorialized, his sister Amanda Beamah Jackson passed away from influenza at the age of 33. Amanda Beamah Barnette was a 1911 graduate of Peabody High, and the mother of three young children, the youngest being Romaine Jackson, who was only eleven months old at the time of her mother’s death. Romaine would grow up and later marry a young man named Earl Childs in October 1941. I mention this couple here because Earl Childs went on to serve in World War II, completed his degree at the University of Pittsburgh in 1953, and practiced general dentistry in the Homewood-Brushton area of Pittsburgh for more than 40 years. This couple’s son, Dr. Earl Douglas Childs, the grandson of Amanda Beamah Jackson, also became a dentist and talked with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette about his own father’s military service. Before Dr. Earl Childs death in 2004, he told his son of the racism and discrimination against African Americans in the military, and in society, during the Second War, and upon returning to Pittsburgh after the war, his employers refused to pay him while he attended college even though they offered that program to white GIs.2 We don’t know why John Barnette did not continue on with his education at the University of Pittsburgh after returning from the war. Did he stop his education to help support his mother, or did he face similar racial discrimination as experienced by Dr. Childs? The answers here would only be speculative.

The 1940 census does reveal that John Barnett was living without his wife at the Pacific Tavern on Frankstown Avenue in Pittsburgh. He died on May 3, 1942, at the age of 48 from tuberculosis; his death certificate indicates that he was separated from his wife at the time and working as a floor crane man at the Homestead Steel Company. He was later buried next to his parents, and sister Amanda Beamah, in the Allegheny Cemetery, in the Lawrenceville neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

It was not until 1948 that President Harry Truman issued an executive order to desegregate the military. The lessons we can learn about the treatment of African Americans during the Great War, and the years following, remains relevant today as our nation continues to struggle with racial disparities. Before researching the history of Barnette, I was more familiar with the notoriety of the famous 369th Infantry unit known as the “Harlem Hellfighters,” a regiment of the 92nd Division that is often highlighted when looking for examples of the black soldier experience during World War I. However, I was not familiar with the operations performed by the 368th Infantry and I am grateful to have learned about John Fountain Barnette Jr, a Pittsburgher that we can be proud to honor and remember for his service as an American soldier; he is not forgotten.

1 1915, February 1. Pittsburgh Schools an Index to City’s Greatness. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, p. 12.

2 Srikameswaran, A. (2004, April 29). Obituary: Dr. Earl Childs / Longtime East End dentist; decorated soldier. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved from https://www.post-gazette.com