Article reposted with permission by the author: Sergeant First Class Aaron L. Heft, USA

Mestrovich, who often went by the name Jack, was born Joko Meštrović on 22 May 1894 in what is now Montenegro, immigrated to the United States in 1911, and eventually settled in California with his uncle and brother. He was a well-known member of the Serbian community in Fresno and worked as a bookkeeper and auditor. Mestrovich later found employment at several hotels in California before eventually making his way to the “Steel City” of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

In 1914 Serbia and much of the Balkans were facing a pandemic much like today. In this case, it was typhus that swept through the region, beginning in camps of the Serbian Army and, in turn, spreading rapidly through the civilian populace. Back in the United States, growing concern about the Serbian people’s fate led aid organizations to begin deploying to the region. A group of volunteer doctors and nurses assembled in the United States through the Red Cross to provide critical medical personnel to Serbia. Mestrovich joined the delegation as an interpreter and spent fifteen months in Serbia on the pandemic’s front lines. While there, Mestrovich witnessed the typhus outbreak and the horrors of modern warfare. In addition to his linguist duties, he assisted his fellow countrymen wounded on the battlefield. Mestrovich once aided a Serbian captain and famous Belgrade professor who later visited him back in Pittsburgh while the captain recuperated there in 1917. American members of the Red Cross did all they could for the Serbian people. In the process, the majority of the group was infected, with a third of the American surgeons and many of the nurses in the group giving their life to aid the Serbian people.

Mestrovich returned to his newfound homeland after the Red Cross mission with a growing sense of patriotism. He told a reporter, “Before I went back home with American Doctors and saw the loyalty with which they served humanity did I (sic) understand the meaning of Americanism.” Upon returning to Pittsburgh in 1916, Mestrovich marched to his local recruiter and joined Company C, 18th Infantry, Pennsylvania National Guard—commonly known as the 18th Pennsylvania Infantry. “After the Americans did this for my people, maybe you can understand why I am in the National Guard. I left a good job as a bookkeeper at a hotel in Pitts- burgh to serve my country’s savior. I am ready for any service the United States has for me.” His country would be calling soon. In June 1916, Mestrovich’s unit was mobilized to serve along the U.S.-Mexico border in support of Regular Army operations in Mexico to apprehend the Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa. The regiment promoted the young immigrant to corporal after he showed his military experience gained with the Serbian Army in his younger years. While the border operation offered Mestrovich an opportunity to serve his nation, the United States soon mobilized his regiment for a much bigger operation.

On 13 April 1917, one week after the United States declared war on Germany, the 18th Pennsylvania Infantry was called up for federal service to guard vital wartime industry in western Pennsylvania. A short time later, the men of the 18th Pennsylvania Infantry found themselves shipped to Camp Hancock near Augusta, Georgia. Here, the Pittsburgh Regiment joined the men of the 6th Pennsylvania Infantry from Philadelphia and sur- rounding counties to form the new 111th Infantry Regiment, which was assigned to the 28th Division. Mestrovich was not the only foreign-born soldier in the regiment. In Mestrovich’s Company C, the roster included other immigrants like Private Vincenzo Ferranti, who enlisted in the National Guard in Philadelphia but was born in Istrocsso, Italy, or Private James Jablonsky of Poland, who joined the National Guard in Pittsburgh. Many men who left their place of birth for end- less opportunity in the United States felt a similar call to arms and joined the Army as Mestrovich had.

After training in the United States, Mestrovich and the rest of the 28th Division, under the command of Major General Charles H. Muir, set sail for France from Camp Upton, New York, in the spring of 1918, with the last elements of the division arriving in France via England on 11 June. Now assigned to the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), the 28th went through a brief period of training with French troops before being rushed to the front in response to the German offensives in the spring and summer of 1918.

Fighting in France, the 28th Division earned the nickname “Men of Iron” for their dramatic stand at the Second Battle of the Marne in July 1918. For Company C and the rest of the 111th Infantry, it would be another fight, the battles for the French towns of Fismes and Fismette, where the men would truly be tested. On 9 August, the soldiers of the 111th relieved the 112th Infantry, which had suffered heavy casualties holding the bridgehead on the southern bank of the Vesle River at Fismes. Some of the companies filtered across the bridge into Fismette itself, on the northern bank. In Fismette, the men of the 111th occupied basements and cellars, fighting from concealed positions as German artillery and machine-gun fire raked the streets. As one lieutenant in Mestrovich’s battalion recalled, “We arranged a regular system of reliefs, the men taking turns on the line, then in the dug-out. To crawl out onto that line among the dead men by the wall in the tense darkness, shells whistling and falling, and now and then a flare of a corpse-like light, was a terrific test for a man.”

town of Fismes in August 1918. (National Archives)

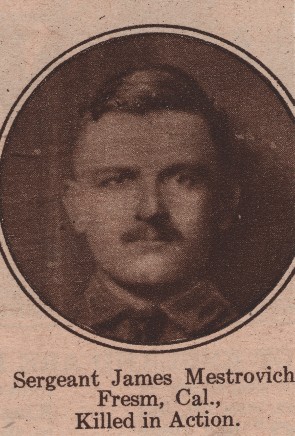

It was here in the hellscape of Fismette that Mestrovich, now a sergeant, forever cemented his name in history. On 10 August, Mestrovich saw his company commander, Captain James Williams, fall wounded as the company moved through the ruins of the town.

Without regard for his own safety, Mestrovich charged forward through a hail of machine-gun fire and falling artillery shells to rescue Williams and carry him to a concealed position to provide life-saving first aid.

Medal of Honor Citation

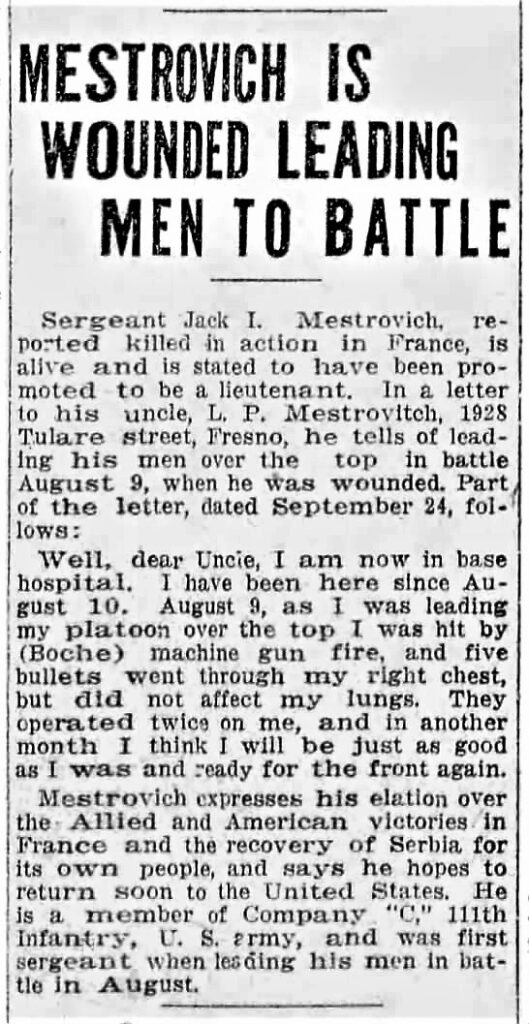

Without regard for his own safety, Mestrovich charged forward through a hail of machine-gun fire and falling artillery shells to rescue Williams and carry him to a concealed position to provide life-saving first aid. For this action, he would become the 28th Division’s first Medal of Honor recipient and one of only 121 soldiers to be awarded the medal in World War I. In rescuing Williams, Mestrovich was seriously wounded and initially reported as killed in action. He wrote to his uncle back in Fresno to tell him of being hit by machine-gun fire and recuperating in the hospital, stating, “They operated twice on me, and in another month I think I will be just as good as I was and ready for the front again.”

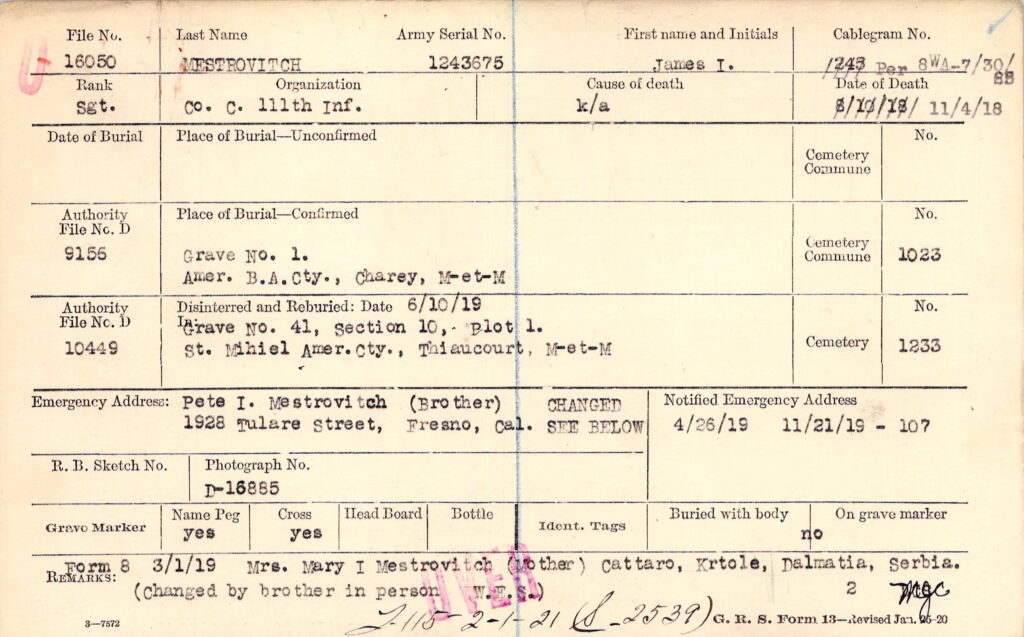

Mestrovich did recover and return to the 111th Infantry, but he would not survive the war to receive recognition for his heroic deeds in the streets of Fismette. As the fighting raged in the Meuse-Argonne, Sergeant Mestrovich fell in action on 4 November 1918 with nearly fifty other men from the 111th when their battalion came under fire from a concealed machine-gun position during a reconnaissance patrol only one week from the end of the war.

After burial in a temporary cemetery in France, Mestrovich was returned home to his mother in 1925 in the town of Boka, Yugoslavia, now in the nation of Montenegro. That same year the U.S. mission to Split visited Mestrovich’s mother and presented her with his Medal of Honor in the presence of a full honor guard. Mestrovich, who had been inspired by the American doctors who traveled to his homeland to provide aid, joined the National Guard to serve his adopted country. In its moment of need, he courageously gave his life in the pursuit of American ideals. Though buried in his homeland of Montenegro, his spirit and patriotism live on in the record of the 111th Infantry and show the real contribution of so many “new Americans” in the AEF during World War I.

This article first appeared in the December 2020 issue of On Point The Journal of Army History, titled “Soldier: Sergeant James I. Mestrovich”