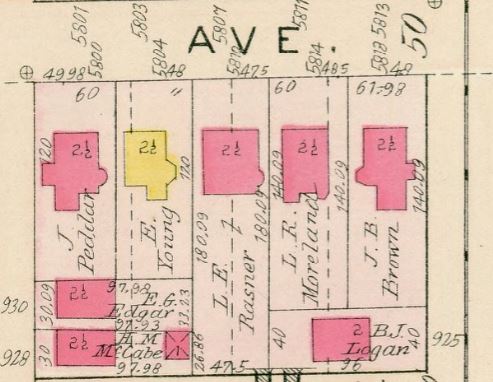

William Ford Moreland was yet another Pittsburgh veteran of the Great War who put himself at risk to assist the Allies before the United States even declared war on Germany. While Moreland survived several battle engagements and returned home, he died prematurely at the age of 36 years as a result of the lasting effects that the war had inflicted upon him. Moreland, who went by the name “Ford” by friends and family, was the son of a prominent Pittsburgh family. He was studying at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut when the war started in Europe. He left the United States to assist as a volunteer with the American Field Service and ultimately worked his way into fighting alongside the French. The Moreland family lived in the present-day Highland Park neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

After the war, he was well known to other veterans of Pittsburgh, such as Colonel Joseph H. Thompson, the state commander of the American Legion, who asked Moreland to be one of his personal aides when Marshal Foch planned his visit to Pittsburgh in November 1921. I’ve included an article here that appeared in the Pittsburgh newspapers that described Morleand’s experiences and have included some photos from the time period that are appropriate to the story. The following article was written by Charles J. Doyle in Paris, December 7, 1918, as a special correspondent of the Pittsburgh Gazette Times while in France.

HEROIC PITTSBURGH BOY BRAVES DEATH TO STOP HUN HORDE – Lt. Moreland’s Remarkable Gallantry Wins Croix de Guerre with Star and Enviable Place in Ranks of Famous Foreign Legion.

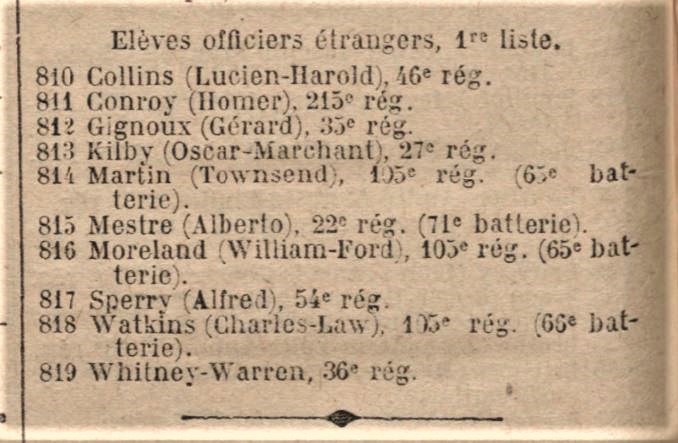

Of the many stories of Western Pennsylvania youths who rushed to France to fight with her for the noble cause of world liberty, which have been coming to light since the war ended, none is more interesting or varied in episode than that of young William Ford Moreland of Pittsburgh, whose father is secretary of the Jones & Laughlin Steel Company. Young Moreland is a lieutenant of artillery in the far-famed Legion Etrangere, or Foreign Legion, of the French Army. He wears the insignia of the Croix de Guerre and star for valor, the decoration having been bestowed upon him in the field by Marshal Petain, at the time commander of all the French armies.

Lieut. Moreland is the youngest officer by several years in the artillery unit to which he is attached, and has been in more battles and swifter action and tighter places and through greater hardships than most other young men of the United States who valorously came to France to help her fight off the Hun horde. His story was told to me by some of the other young Americans here, who know his record, which is said to be unusual and which France has recognized by several decorations.

As soon as war was declared between American and Germany young Moreland, then a student at Yale University, started out to get into Uncle Sam’s fighting forces and be sent over here. As he was not yet 20 years old, he was unable to enlist in any officers’ training camp of the American service in any capacity, although he tried them all. However, he came to France with the American Field Service toward the end of June, 1917, enlisting to drive an ambulance or transport.

William Ford Moreland AFS photo c1917

William Ford Moreland Passport photo c1919

After he got here and looked around, he decided that he would see more action and be of more service by joining the French Army transport, which he did. He was sent to a training camp and engaged in a short while as a full-fledged driver, or “conducteur,” of a five-ton French Army truck. Moreland’s company was sent to supply the famous French 75s in the artillery duel on the Verdun and Champagne fronts, and it was while so engaged that he received his first citation for courage in going to help serve a gun which had become shorthanded by reason of casualties during the action. His work with the transport service, hazardous and hard and frequently under fire, brought him in contact with the artillery at the front and caused him to determine to get into that branch of the French service.

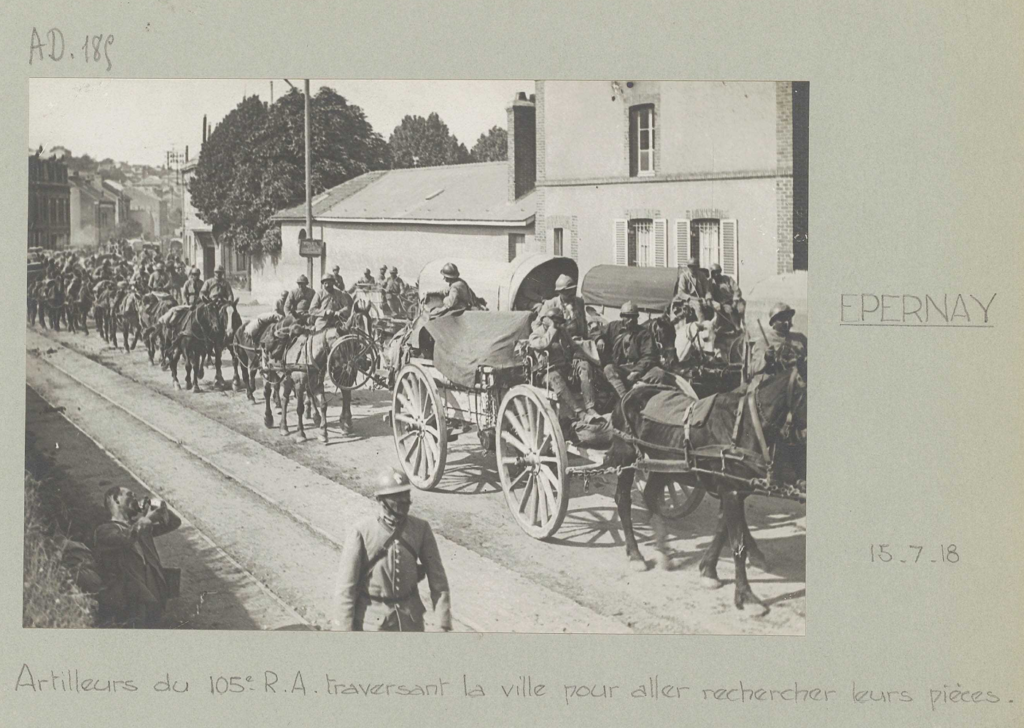

Leaving the transport, he enlisted in the French artillery as a private, but was shortly taken out and sent to the officers’ training school at Fontainebleau, near this city [Paris], where he trained for artillery aviation. He passed successfully the severe tests of the school and was sent to train for the flying service. Just as he had completed his training as an airman volunteers were called for in the new French tank service and Moreland stepped forward. However, before he could be fully trained for this branch of the service he was selected on merit for the artillery of the Foreign Legion, and from the moment of joining his battery was engaged in action, which continued up to the signing of the armistice with little respite. The battery to which he was originally assigned was decimated in one of the great West front battles and Moreland was transferred to another command, which was badly used up in the closing engagements of the war, losing nearly all its horses and sustaining heavy casualties among officers and men. From the start of the great Allied offensive which brought end of the war Lieut. Moreland’s battery was at the front, following closely after the advancing infantry to furnish barrage fire and obliterate enemy trench systems and repel counter-attacks.

DECORATED FOR BRAVERY The act for which Lieut. Moreland was decorated in the field was one of exceptional coolness and deliberate sacrifice. His work of acting as barrage officer obliged him to go forward with the infantry to direct the barrage fire so that it remained always in front of the troops. This was done by means of a telephone mounted on wheels and required quick thinking and accurate calculating in order to avoid the catastrophe of the infantry rushing into its own barrage and also to prevent the enemy from coming through it.

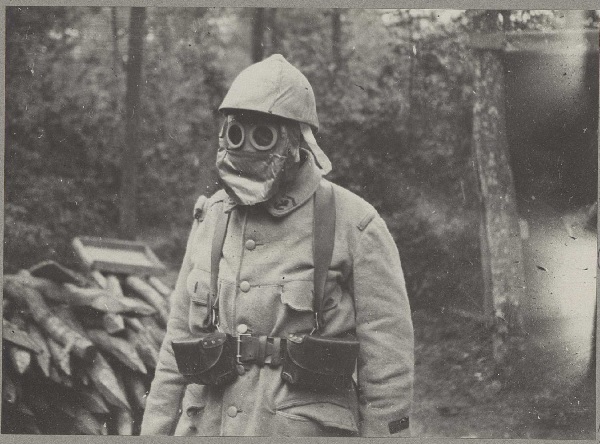

On the occasion mentions Lieut. Moreland was far out ahead with the first saves of infantry going forward in a heavy field of gas. Suddenly he saw a mass of enemy troops arise out of the trenches only a few hundred yards away and start forward in counter-attack. Quick work was necessary to alter the range of battery fire and check the attacking wave of Huns. He tried to give directions over the telephone, but the difficulty of making himself understood through the gas mask was too great. Instantly and deliberately, he removed the mask and transmitted the proper orders. He managed to get the mask on again, but succumbed to the gas. The advancing French found him unconscious and removed him to a dressing station. Here he was brought around and sent back and finally ordered up to this city on furlough to fully recover.

COMMAND IS SAVED Official records show that, as a result of Lieut. Moreland’s prompt and heroic action in risking his life to save his comrades, the battery was able to lay down a heavy barrage on the Huns within eight seconds after his telephone message got in and the attack was completely checked. For this deed of coolness, he was awarded the Croix de Guerre with star, which indicates a double award, and had the further distinction of having it pinned on his breast before the troops by Petain.

At the time this occurred Lieut. Moreland was a lieutenant aspirant, but having notable passed through the probationary period has since been promoted to a lieutenancy. His experience in the Great War just ended has been that of many other clean, courageous, high-minded young Americans, but few of them have been privileged to serve with the French artillery in the world-famous Foreign Legion and fewer still have been in as many battles and experienced as many exciting adventures with accompanying thrills.

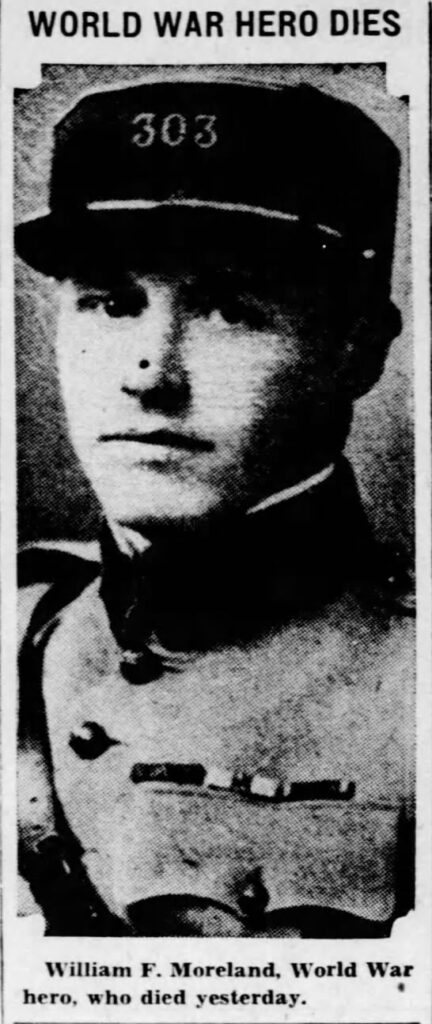

WILLIAM FORD MORELAND, HERO OF WORLD WAR, DIES HERE – Dared Effects of Poison Gas To Direct Fire That Saved Comrades – this article appeared in the Pittsburgh Press on February 27, 1933.

Legionnaires Mourn – Moreland was Honored by French Government With Special Croix de Guerre. The French Foreign Legion has lost one of its most gallant heroes in all its reckless history with the death of William Ford Moreland. Vice president of the Interstate Iron Company, a subsidiary of Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation. Mr. Moreland, whose distinguished war service amounted to a brilliant record overseas in the World War, died yesterday after an operation. In France there are scores perhaps hundreds of Legionnaires who will mourn his death, for they owe their lives to the heroism of the Pittsburgher during one of the major Allied offensives.

Honored for Heroism – After this deed Mr. Moreland one day stood in a field before his comrades in arms, who cheered as the French leader, Marshal Petain, pinned on his breast a French Croix de Guerre. There was a star on that medal, indicating a double reward. “Deliberate sacrifice and exceptional coolness” such was the description of Mr. Moreland’s action which saved a group of French infantry from German bayonets and guns. As a member of the French Foreign Legion, Mr. Moreland at the time was a “barrage officer.” His duties were to go ahead with the first waves of the infantry to direct artillery fire.

Germans Surprised – The French shells were falling a few hundred yards ahead of the advancing French. Suddenly out of a trench hundreds of Germans appeared ready for the counter charge. Gas shells were dropping all around. The French fire was falling beyond the Germans. Mr. Moreland had to notify the artillery battery to change its fire to stop that counter charge. But how? Poison gas was all around him. He was wearing his mask. He could not talk into a field telephone-mounted on wheels while he had that mask on.

He ripped off the mask and gave the news through the phone. The French battery immediately poured a deadly barrage on the Germans and stopped their rush.

Pittsburgh Press (Pittsburgh PA) February 27, 1933

Found Overcome on Field – He ripped off the mask and gave the news through the phone. The French battery immediately poured a deadly barrage on the Germans, and stopped their rush. French infantry found Mr. Moreland overcome beside the field telephone the receiver in his hand. He was hailed immediately as a hero who had risked his life so save his fellow soldiers. Not yet 20, and while a student at Yale University, Mr. Moreland went to France with the American Field Service, and enlisted in the French Ambulance Corps because his youth barred him from enlisting in an officers’ training camp in the United States. He joined the French Army transport, and was sent to a training camp at Fontainebleau. Next, he was driving an ammunition truck in the great offensives at the Verdun and Champagne fronts. He was cited for courage when he manned a service gun, short-handed by casualties.

Made Lieutenant – He then joined the French artillery as a private, fighting in all major offensives until the Armistice. He was made a lieutenant soon after he became an artilleryman, in the Foreign Legion. Mr. Moreland was born in Pittsburgh in 1896, and attended Shadyside Academy and the Hill School as preparation for Yale. He entered the Yale class of 1913.

Rises in Industry – On his return from the war he went to Virginia City, Minn., for two years as the representative of Jones & Laughlin at the iron ore mines. Then he returned to Pittsburgh, and was finally made vice president of the iron concern. His father is secretary of the corporation. Mr. Moreland is survived by his widow. Mrs. Helen Snow Moreland; two children. Barbara and William Crawford Moreland III; his parents, Mr. and Mrs. William C. Moreland; and a brother, Raymond Ford Moreland, Pittsburgh attorney.

The Pittsburgh Press (Pittsburgh, PA) Feb 27, 1933. p.28