The First Aviators

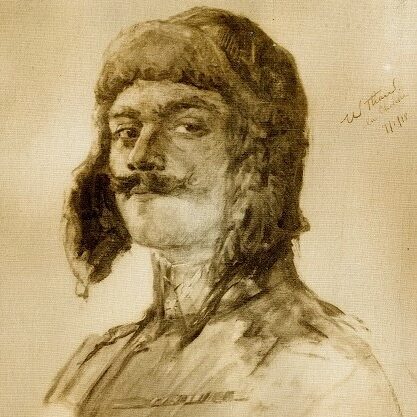

Pittsburgh can be proud of one of its own citizens playing an important part in the early days of the Great War, and notably, becoming the first American to receive the French Légion d’honneur (Legion of Honour), the highest military award given by the French Government. The honor itself dates back to the time it was first established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1802. The gentleman credited with this distinction was a young man from Pittsburgh named William “Bill” Thaw II.

Thaw, only 21 years old when the war began, put himself in harm’s way numerous times to assist the French in their fight against Germany. He started the war in the trenches volunteering as an infantry soldier, flew in a French aero squadron, and ended the war representing the United States as a decorated American aviator. So how did a 21-year-old Pittsburgher get into such a situation? In his case, he volunteered for the service.

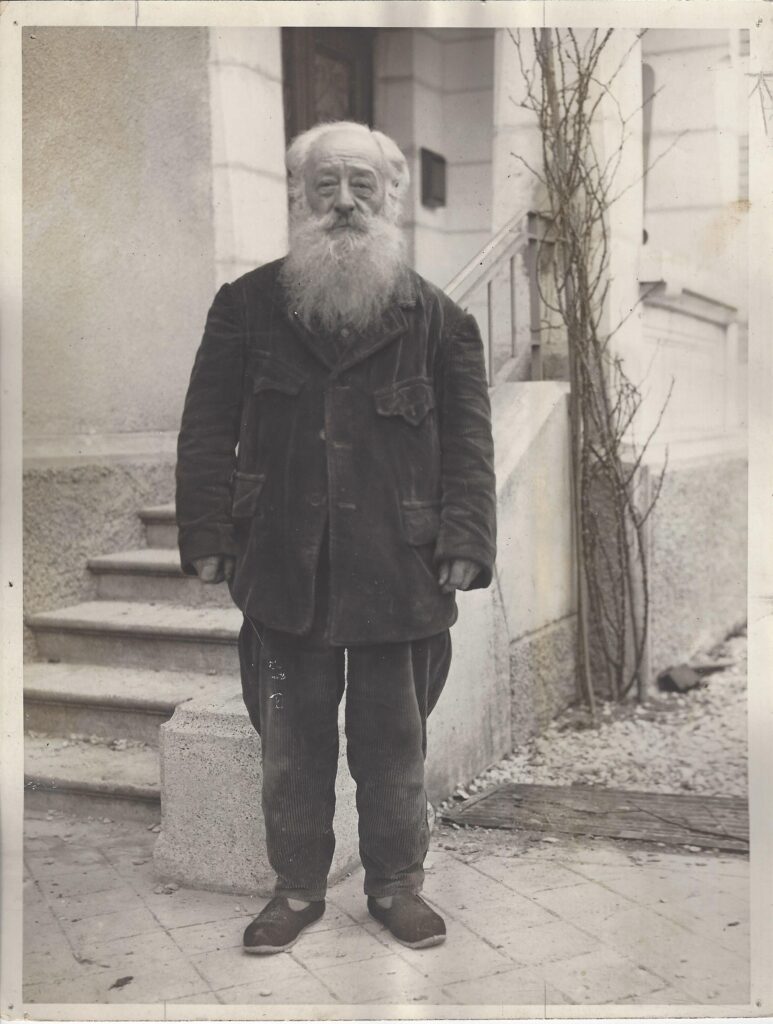

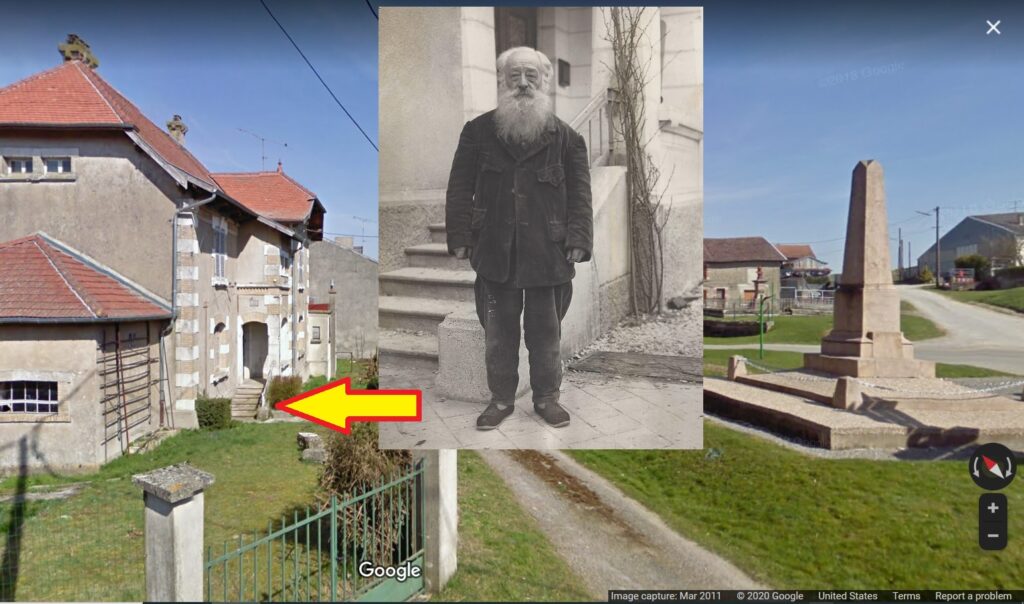

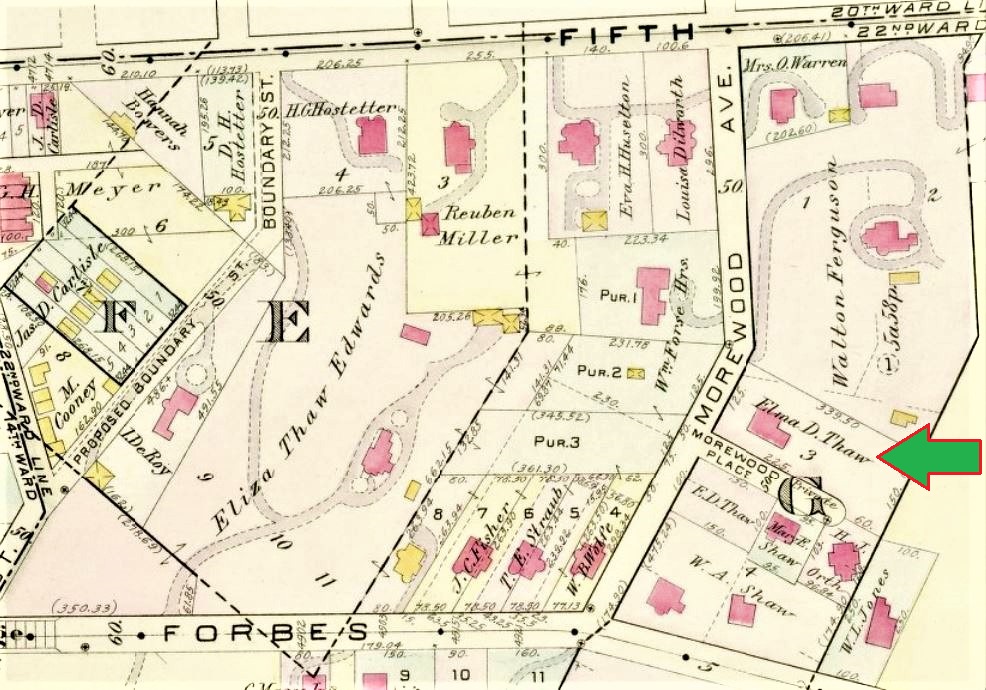

Thaw was born into a wealthy Pittsburgh family. His grandfather, William Thaw Sr. made his fortune in canals, the coke industry, and railroads. His father Benjamin Thaw, managed his late father’s estate and was himself a successful banker and trustee. His mother, Elma Dows Thaw, kept the family residence in the Squirrel Hill North neighborhood of Pittsburgh at Moorewood Place. The dwelling no longer exists, but it would have been located on the present-day grounds of Carnegie Mellon University (the Greek Quad). The Thaw Family also had a residence in New York City where the family would often spend time.

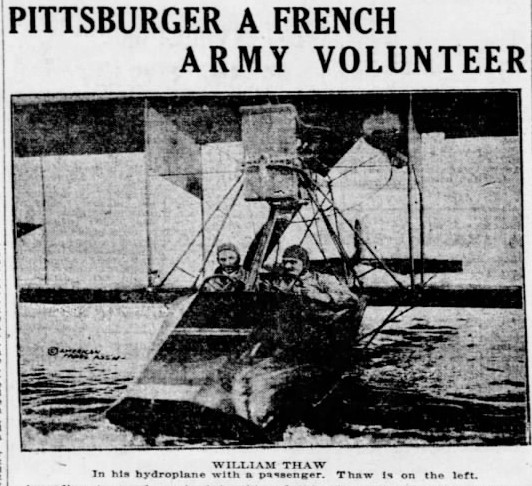

Bill Thaw dropped out of Yale in his sophomore year, took flying lessons, and began a small business/hobby of flying passengers in New York City, once even flying his Curtiss hydroplane under four of the bridges located on the East River without touching the water. When the war began in 1914, Bill Thaw was already in France. He was there to compete in an organized race of seaplanes known as the Schneider Cup. Thaw donated his plane to the French War Department and offered his services to the French air service, but his initial offer to serve was rejected. Undeterred, he enlisted in the French Foreign Legion and served in the battlefront trenches for several months. An American correspondent with the volunteers wrote about their experiences in November 1914, “The second line trenches are rather more comfortable than the ones we have had before, as they have a fire in them. We got many good things in the shape of food that evening. It is reported that tomorrow we are going for a rest where we hone to find baths. Life is the same day in and day out. Nevertheless, it is exciting because of the danger in the presence of the inevitable shell.”

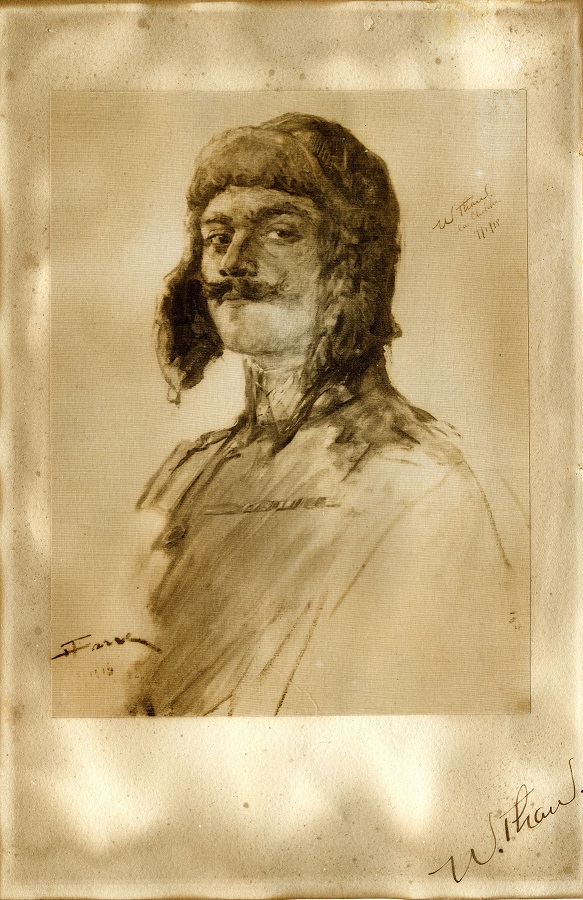

Life in the trenches did not give the young Thaw the pace of excitement he was seeking and he made his way to convince the commander of an aero squadron for an opportunity to transfer into that unit where he could provide his aviation knowledge and skills. Thaw was granted a transfer out of the French Foreign Legion and into a French aero squadron, given the role of a “soldat mitrailleur,” or soldier machine gunner. This placed him as an observer in a plane where he carried a pistol and machine gun as the pilot made runs to spot enemy movements (machine guns were not yet mounted). Some descriptions of his activities at this time report that this role as an observer-gunner inside the plane may have likely made him the first American to take part in aerial combat during the war. Thaw would serve in this role for a year, commended for his abilities, and eventually become the first American to be promoted a “sous lieutenant” or second lieutenant in the French military. Thaw was finally able to prove his flying abilities to the French superiors and was permitted to puts his flying skills to the test.

Thaw would partner with another American volunteer, Norman Prince, the son Frederick H. Prince, a wealthy American banker from Massachusetts. These two young men joined forces, with the support of other Americans sympathetic to the French fight against Germany. They convinced the French War Department to give the young Americans a chance to fly as their own squadron. The French word for a squadron is ‘escardon or escadrille.’ In 1916, a year before the United States entered the war, the French Government approved of the American volunteer squadron, under the leadership of a French commander, to form the “Lafayette Escadrille.” The name Lafayette used in honor of Marquis de Lafayette, the French military officer who came to America to fight in the Revolution.

Most people familiar with the topic of World War I have undoubtedly heard the phrase “Lafayette, we are here,” words that were said to have been spoken at Lafayette’s tomb when the United States arrived in France in 1917. These few words were an echo of the sentiment as to why the Americans were there to help the French people. In 1825, Marquis de Lafayette was actually in Pittsburgh on a tour of the United States. He was the guest at a reception given by Mayor Charles Shaler. Lafayette had this to say: “So, in the very time of the revolution, Pittsburgh has proved very interesting to us as a military post, nor can I recall those transactions, without gratefully remembering that my name has been associated with its military existence as a fort.” Lafayette was referring to a colonial fort that was located near present-day Penn and Ninth Streets. He was undoubtedly proud to have had his name attached to a military fort in Pittsburgh, and 92 years later, a young man from Pittsburgh would attach his name to another military entity, representing a group of Americans looking to honor and return the favor of his deeds.

Perhaps the pinnacle of William Thaw’s performance as an aviator came when the French government bestowed upon him the “Chevalier of the Legion of Honor.” The citation reads, “A volunteer for the duration of the war. A pilot remarkable for his skill, his spirit and contempt of danger. Has recently delivered 18 aerial combats at short distance. May 24 at daybreak he attacked and destroyed an enemy plane. The same evening, he attacked a group of three German machines and pursued them from four thousand meters of altitude down to one thousand. Painfully wounded during the combat, he succeeded, thanks to his daring and his energy, and bringing into our lines his gravely damaged aero plane and landed normally. Already twice cited in the Order of the Army. This nomination carries with it the Croix de Guerre with palm.”

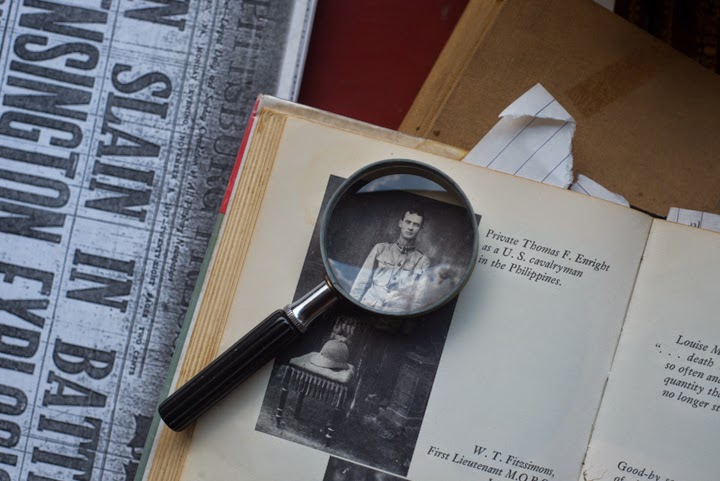

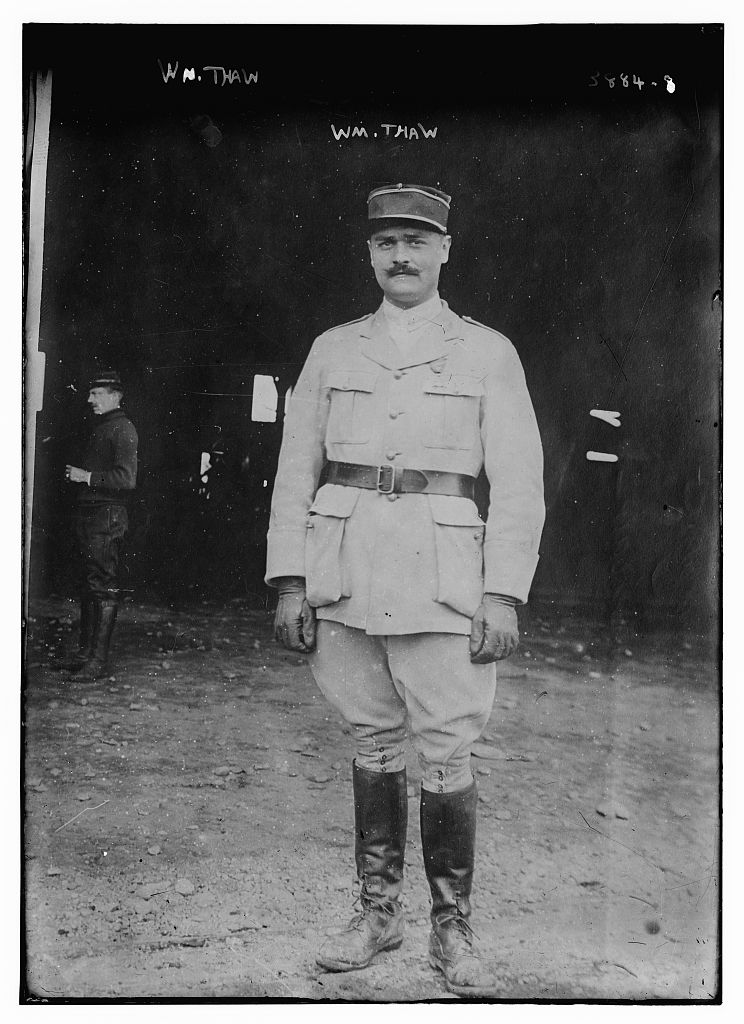

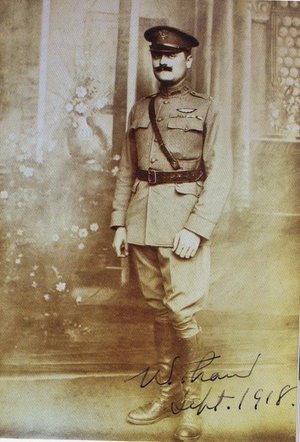

One of the more striking photos that I have seen of William Thaw in France is when he is surrounded by members of the Layfette Escadrille, holding an American Flag that was made by employees of the US Treasury Department. The flag was passed to the French Ambassador via Eleanor Wilson McAdoo, daughter of President Woodrow Wilson. Her husband was Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo. Thaw is pictured here wearing his French uniform. However, once the US entered the war, the Lafayette Escadrille would later become the 103rd United States Aero Squadron. The photo that follows shows Thaw in his uniform for the United States where he would eventually be promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

After the war, Lt. Col William Thaw returned to Pittsburgh and married Marjorie E. Priest in 1921. The couple lived in the Schenley Apartment (now a dormitory for University of Pittsburgh students). He went into the insurance business but died prematurely in 1934 of pneumonia at just 40 years of age. He is buried in Allegheny Cemetery in Lawrenceville.

Bill Thaw lost his younger brother who was also serving during the war. Alexander Blair Thaw was an aviator in France and was killed when his plane was caught in some wires and the aircraft crashed to the ground on top of him. I will explore Alexander Blair Thaw’s service in a separate article.

There is no shortage of material available to read about the Lafayette Escadrille and William Thaw II. My goal here was to introduce the topic of this Pittsburgh aviator to anyone unfamiliar with his story. He was indeed an interesting man who played a vital role in a noble cause. Please take a look at the YouTube video about the “Lafayette Escadrille.” I’ll end this article with an observation by Edwin C. Parsons, a former French Foreign Legionnaire and WWI pilot who served with Thaw. “Bill was without question the most striking and popular figure on the front. There was never a dull moment in his company. It seemed as if there weren’t a man, woman or child from Dunkirk to the Voges who didn’t know ‘Meester Beel Taw’; not only know him, but love him.”

Image was released by the United States Air Force with the ID 141006-F-DW547-001